Cardiac surgeon Amy Fiedler, MD, stares at the motionless heart below her in an operating room at UC San Francisco’s Helen Diller Medical Center at Parnassus Heights.

She’s nearly five hours into a heart transplant surgery. The procedure is one of medicine’s most complicated, demanding some of surgery’s longest operating times and a highly specialized team. It is also some heart failure patients’ last hope.

With the donor heart now in place, Fiedler carefully removes a clamp on the heart’s largest artery, the aorta. Within seconds, blood rushes down through the vessel, filling the organ.

The heart, silent and still seconds ago, begins to beat.

“No matter how many transplants I do, nothing will ever amaze me more than watching the donor heart beat in the recipient after the clamp comes off,” Fiedler would later say.

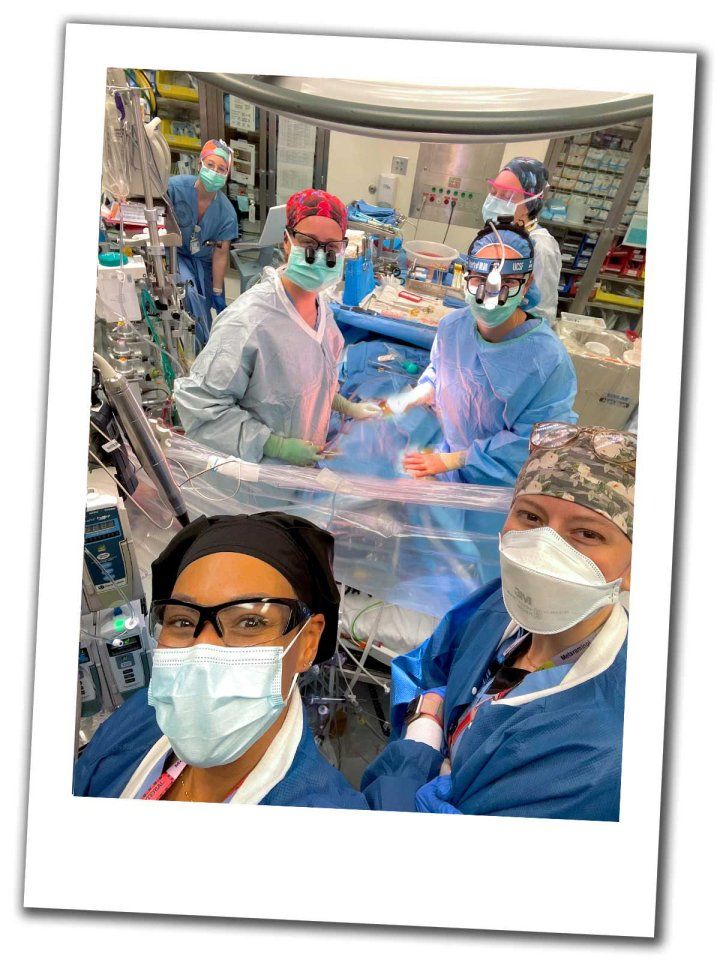

As the team prepares to shift the patient to the intensive care unit. Fiedler pauses, turning her head, taking in the room — a moment that UCSF Anesthesiology Professor Charlene Blake, MD, PhD, would later recount to television crews.

It dawns on Fiedler: “We’re all women …” Click. The group takes a selfie.

A plane, a plot twist, and a legacy

As a young surgery resident, Fiedler imagined a future in pediatrics or oncology — until a birthday spent on call changed her life. A donor heart became available that day, and she joined her hospital’s sole female heart-transplant surgeon, Jennifer D. Walker, MD, on a plane to retrieve the organ.

Women comprise less than 6% of U.S. heart transplant surgeons, making it one of medicine’s most male-dominated specialties. The gender imbalance is perpetuated by gaps in pay, mentorship, leadership opportunities, and even patient referrals. Women must also balance long hours and intense training with decisions about family-building, particularly early in their careers. But it’s not just women who lose in this equation: When health care workers reflect society, patient care improves — as do institutions’ innovation, productivity, and financial health, research shows.

But Walker, at 30,000 feet in the air, still managed to convince Fiedler that she, too, could become a transplant surgeon. Walker backed her promise with action, training her like an athlete, Fiedler says.

Fiedler would become the second female heart transplant surgeon to graduate from Massachusetts General Hospital’s residency program. “I remember as a resident, sitting in the conference room, and on the walls, there were rows of headshots of the graduated residents. It was all men — and then there was Dr. Walker’s photo,” she says. “Twenty-five years later, there was mine.”

In 2022, Fiedler led what is likely the world’s first all-female heart transplant at UCSF. The selfie immortalizing the historic moment went viral — inspiring other women to share their own on social media.

Today, Fiedler is UCSF’s first female heart transplant surgeon and the Surgical Director of Heart Transplantation and Mechanical Circulatory Support. Together with UCSF’s Advanced Heart Failure Comprehensive Care Center, she is pioneering the latest technology to ramp up life-saving care for heart failure patients. And all these years later, she is paying that plane ride forward, mentoring others, particularly women, as part of UCSF’s work to transform the face and culture of surgery.

The mentorship multiplier

If someone wants to do this, by all means, I’d like to help them get there.

Amy Fiedler, MD

It’s a chilly spring morning in April, and fog gathers around UCSF’s Medical Sciences Building. On the third floor, Fiedler has just returned to her office after an emergency operation. Behind her on the wall are keepsakes: a framed copy of a news article detailing her 2022 all-female surgery, a memento from her work with the nonprofit Team Heart to improve access to cardiac surgery in Rwanda, and an Ironman Triathlon bib.

From the hallway, Division Chief of Adult Cardiac Surgery and Lung Transplantation Jason W. Smith, MD, pokes his head through her doorway. The two share a laugh with the easy cadence of people who’ve spent years trading ideas across hallways, coffees, and conference tables.

The pair met early in her career at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Then, Smith provided mentorship in transplantation and circulatory support. The two worked so seamlessly together that when Smith was recruited by UCSF in 2022, he urged the university to consider her, too. Now, he says, she has become key in transforming the program he heads as UCSF expands access to life-saving transplants.

“Amy is a great surgeon and driven — other surgeons would feel intimidated by that, but I’ve been teaching a long time, so I always felt comfortable giving her space to grow,” Smith says. “She knows I’m not going to step on her tail, and I feel very supported — we have a great partnership.”

In her own words: Meet Dr. Amy Fiedler, the surgical director of the heart transplantation and mechanical circulatory support program at UCSF. She specializes in caring for patients with heart failure, including those who need heart transplantation. Her focus is on restoring patients’ quality of life.

First total artificial heart transplant

Smith and Fiedler are working to revolutionize care at UCSF’s Advanced Heart Failure Comprehensive Care Center under the leadership of cardiologist Liviu Klein, MD, MS.

In 2024, the duo performed UCSF’s first total artificial heart transplant, a technology that Smith helped trial in his clinical research. The machine replaces a heart’s faulty lower chambers, restoring circulation in people waiting for a transplant. The use of this and other technologies is just one reason the center ranks among California’s best in patient outcomes and performs nearly 100 transplants annually. It is also one of the few nationwide that care for heart failure patients at every stage of the disease.

“Amy and I think similarly about transplant,” Smith says. “We’re aggressive but smart about how we approach it and have a desire to grow the program while pushing boundaries.”

Mentorship is only one part of creating a truly welcoming environment — a priority for UCSF Chair of Surgery Julie Ann Sosa, MD, MA, FACS. As the department’s second consecutive woman chair, Sosa has earned national recognition for pushing the field to better reflect the patients it serves. Under her leadership, the department reached gender pay equity in 2024.

“What’s happening within our transplant program reflects the strength of a culture where excellence and belonging are equally prioritized,” Sosa says. “Leaders like Dr. Fiedler are advancing the science while shaping an environment where others can rise with them — that combination is what drives UCSF Surgery forward.”

‘I’d only ever seen one female cardiac surgeon’

An inclusive environment is why Bianca Bromberger, MD, chose UCSF for her cardiothoracic surgery fellowship. “The culture is so welcoming,” she explains. “People are supportive of me as a trainee and my career, but also of the fact that I have a family and life outside of work.”

Bromberger welcomed her second child in May, shortly before becoming an assistant professor of surgery. She is UCSF’s second female heart transplant surgeon.

“Before I came to UCSF, I’d only ever seen one female cardiac surgeon, so just seeing Dr. Fiedler was a shock but also inspiring,” Bromberger explains. “Here was this woman, and she wasn’t just an attending cardiac surgeon, but she was thriving — technically very good, great clinical judgement, confident and decisive.”

Fiedler has incredibly high standards, Bromberger says of her mentor. “She wants you to master one aspect of surgery before going on to the next. Her high standards and advocacy have helped me get to where I am now.”

And that’s by design.

“Mentorship is incredibly important, and I’ve been lucky to have people who were in my corner every step of the way,” says Fiedler, who regularly answers questions from would-be surgeons across the globe. “It’s just such an important responsibility to train the next generation of people who want to commit themselves to the calling you’re passionate about — and you can’t take that responsibility lightly.”

She continues. “If someone wants to do this, by all means, I’d like to help them get there.”