Immunotherapies using engineered T cells have ushered in a new era in cancer treatment, but they have their limits. They may cause side effects or stop working, and they do not work at all against 90% of cancers.

Now, scientists at UC San Francisco and Northwestern Medicine may have found a way around these limitations by borrowing a few tricks from cancer itself.

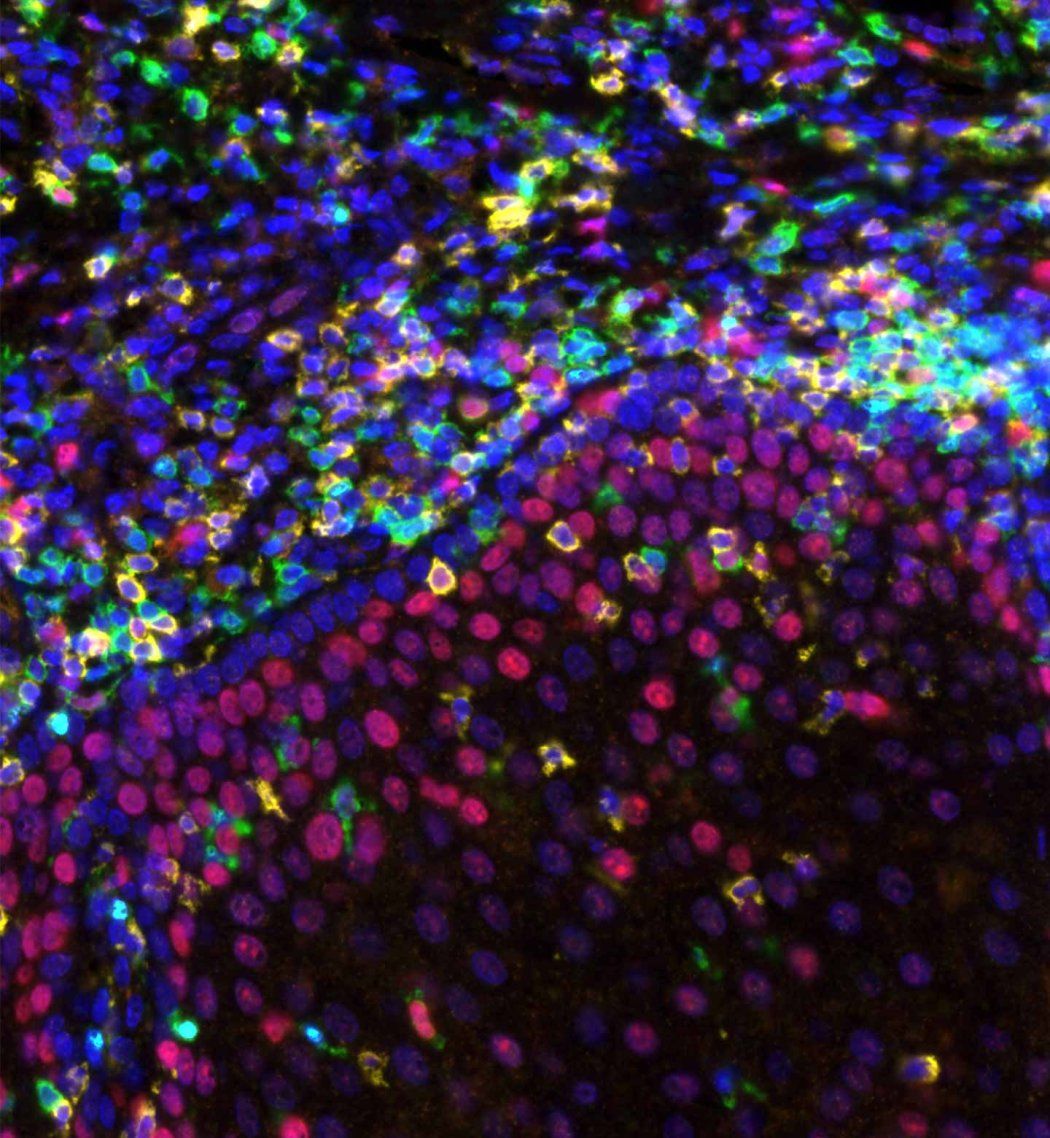

By studying mutations in malignant T cells that cause lymphoma, they zeroed in on one that imparted exceptional potency to engineered T cells. The team inserted a gene for this unique mutation into normal human T cells, which made them more than 100 times more potent at killing cancer cells. They kept the tumors at bay for many months, showing no signs of becoming toxic.

While current immunotherapies work only against cancers of the blood and bone marrow, the new approach was able to kill solid tumors derived from skin, lung and stomach tissues in mice. The team has already begun working toward testing this new approach in people.

The breakthrough was inspired by the martial arts principle of using an opponent’s strength against them, said Kole Roybal, PhD, a co-author on the study and associate professor of microbiology and immunology.

“We’ve used the mutations that give cancer cells their staying power to engineer what we call a ‘Judo T-cell therapy’ that can survive and thrive in the harsh conditions that tumors create,” he said.

The study appears Feb. 7 in Nature.

We need to give healthy T cells abilities that are beyond what they can naturally achieve.”

Kole Roybal, PhD

A solution hiding in plain sight

Immunotherapy has proved difficult against most cancers because a solid tumor creates an environment focused on sustaining itself, redirecting resources like oxygen and nutrients for its own benefit. Often, cancerous tumors hijack the body’s immune system, causing it to defend, rather than attack, the cancer.

Not only does this impair the ability of regular T cells to target cancer cells, it also undermines the effectiveness of engineered T cells that are used in immunotherapies, which quickly tire against the tumor’s defenses. For immunotherapy treatments to work under those conditions, “We need to give healthy T cells abilities that are beyond what they can naturally achieve,” said Roybal, who is also a member of the Gladstone Institute of Genomic Immunology.

Using such T cells from patients with lymphoma, the UCSF and Northwestern teams screened 71 mutations, eventually isolating one that proved both potent and non-toxic, subjecting it to a rigorous set of safety tests.

“This approach performs better than anything we’ve seen before,” said Jaehyuk Choi, MD, PhD, an associate professor of medical dermatology, as well as biochemistry and molecular genetics, at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

“Our discoveries empower T cells to kill multiple cancer types and have the potential to offer cures to people who have a poor prognosis,” he said, noting that because cell therapies live and grow inside the patient, they can provide long-term immunity against cancer.

In collaboration with the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy and venture capital firm Venrock, Roybal and Choi have launched a new company, Moonlight Bio, to realize the potential of their “judo” approach. Their first project is developing a lung cancer therapy that they hope to begin testing in people within the next few years.

“We see this as the starting point,” Roybal said. “There’s so much to learn from nature about how we can enhance these cells and tailor them to different types of diseases.”

The research was supported by the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, NIH grants (grants F30 CA265107, T32 CA009560, 1DP2AI136599-01 and DP2 CA239143), Cancer Moonshot grant U54 CA244438, the Mark Foundation for Cancer Research, the Bakewell Foundation, and UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Roybal and Choi are inventors on patents related to these discoveries and are co-founders and equity holders in Moonlight Bio.