How Dangerous Is Mpox? UCSF’s Seth Blumberg Explains

Editor’s Note: This story was updated on Aug. 2, 2022, to provide updated information.

Mpox, which has been circulating in Central and Western Africa for many decades, has now spread globally, with over 5,000 cases in the U.S. This has fueled more infection fears, no surprise in the wake of the still quite active COVID pandemic.

Mpox can occasionally be deadly, especially in places with inadequate health care, and is closely related to smallpox, which plagued humans for millennia. Smallpox was eradicated due to a worldwide vaccination campaign. In the U.S., mass vaccinations ended in 1972, but the vaccines remain stockpiled.

Mpox has been known since the late 1950s, and despite its name, its natural reservoir is rodents. In the past, it has most often spread between humans through contact with disease lesions, or through exhaled respiratory droplets during prolonged close contact. With the current outbreak, the possibility of sexual transmission is being considered particularly since men who have sex with men account for most cases of the current outbreak.

We spoke to Seth Blumberg, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine at UC San Francisco, who is clinical specialist in infectious disease, as well as a computational scientist who studies the population-level emergence and elimination of disease. Mpox is among the diseases he has studied.

What are the similarities and differences between mpox and smallpox?

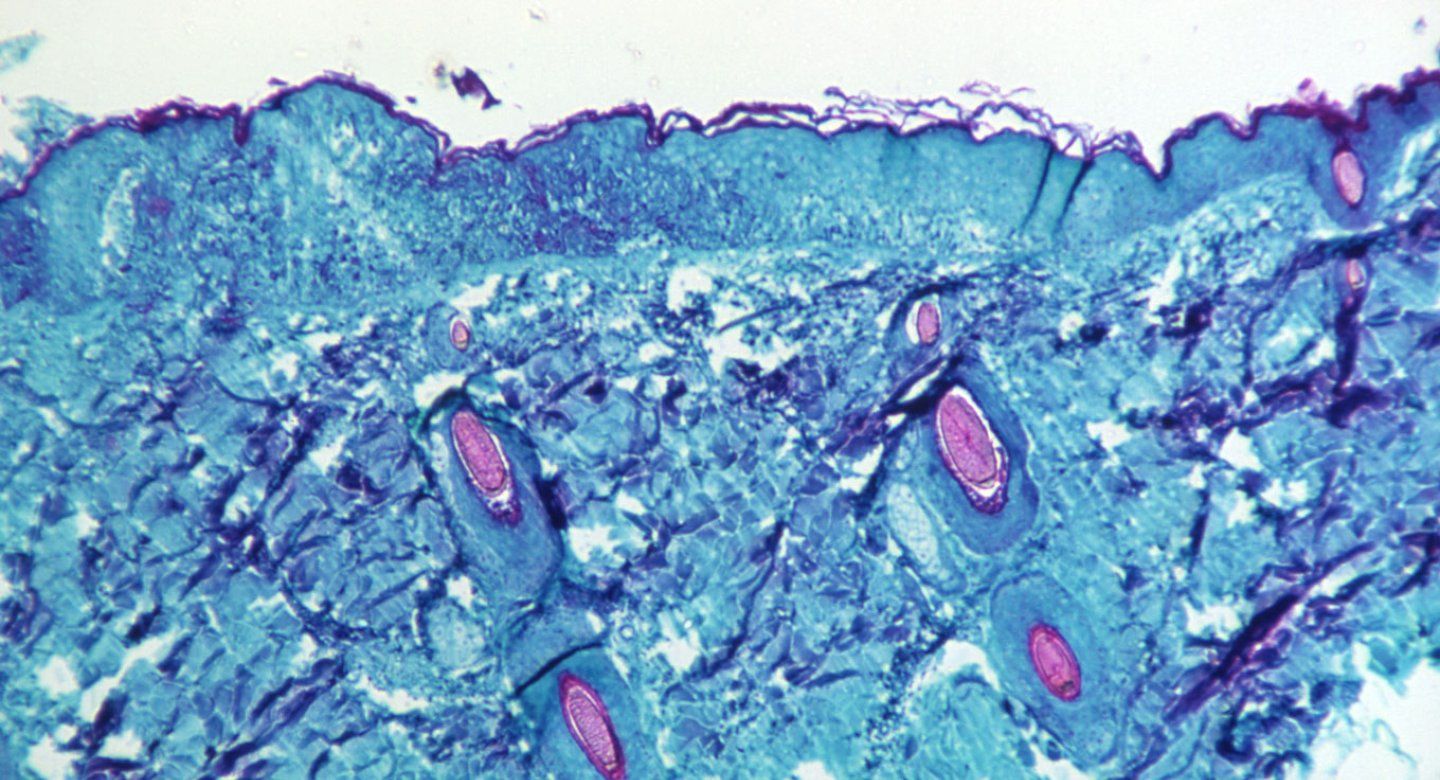

Mpox and smallpox are in the same class of viruses. They share cross-immunity, which means protection against one confers protection against the other. The benefit of this relationship is that vaccinations developed to protect against smallpox also protect against mpox. There is also an overlap in clinical symptoms. Both are associated with fevers, swollen lymph glands, fatigue, and a vesicular rash – a rash with little blisters that may be distributed anywhere on the body and which can look similar to chickenpox. Fortunately, the biggest difference is that mpox is much less disfiguring and deadly than smallpox, and in particular, the Western African strain of mpox, which is circulating now, is less pathogenic than the strain found in Central Africa.

Is mpox becoming more widespread?

We have seen an increase in cases of mpox in recent years in Africa due to a combination of factors affecting both animal-to-human and human-to-human transmission. One key factor is that people are not getting vaccinated against smallpox anymore, so there is some loss of immunity within the population.

Routine vaccination for smallpox in the U.S. ended in 1972. How much protection from mpox do vaccinated and unvaccinated people have?

We are not as protected as we were 50 years ago when smallpox vaccination was common. We don’t really know how much population immunity remains because mpox has not presented much of a disease burden to gauge protection. Hopefully, the elder part of the population is protected from prior vaccination, and there is a good chance that it is based on the age-prevalence of mpox disease in Central Africa. We just don't know for sure. In studies from the 1980s, vaccination was thought to provide 85% protection against acquiring mpox.

How is it that a vaccine developed more than a half-century ago to fight smallpox still is effective today against mpox, while a COVID vaccine developed just a year ago already needs updating?

Viruses have a remarkable ability to change over time by genetically mutating. But the rate of change is different for different viruses. Mpox is a DNA virus, whereas the genetic material in SARS-CoV-2 is RNA. RNA viruses tend to mutate much faster than DNA viruses. As a result, it generally is harder to develop an RNA vaccine that remains effective long-term, than it is a DNA vaccine.

What have you learned from your past studies of mpox and other disease outbreaks in humans and animals?

I think one of the things that mpox demonstrates is the interplay between individual health, people’s habits and behaviors, national health, global health, politics, economics, poverty, wildlife, and climate change. As aspects of the world change, it affects the epidemiology and emergence of diseases.

Most physicians have not seen mpox. Is it difficult to diagnose?

Mpox is one of several diseases that present as a vesicular rash. A trained physician can often identify which disease is most likely. For example, the rash of herpes simplex virus is typically localized to genital or oral regions. Shingles, caused by reactivation of the virus that causes chickenpox, result in a distinctive vesicular rash that usually wraps partway around the trunk in a narrow band and affects just one side of the body. Chickenpox leads to a widely disseminated rash. Mpox can look like these other diseases, but exposure details can help to narrow the possibilities. Because treatment is available for all of these diseases, any new vesicular rash deserves medical evaluation.

Do you have any suspicion that the mpox virus may be spreading differently than it has in the past?

It’s possible that it is evolving in a way that makes it more transmissible. In the current outbreak, some cases have been genetically sequenced and we have not seen major changes. However, the importance of subtle changes can take some time to figure out. We certainly have not previously seen this many cases emerging outside of Africa. Perhaps there are easier pathways for transmission in cities or during large social events where the virus has not been previously present. Although it does not explain why the 2022 outbreak is so large, wildlife changes can also be a factor, such as whether a different animal population has become a new reservoir for the virus.

Is this mpox outbreak potentially a major global health threat, like COVID?

Given the rapid rise of cases and the potential to contribute to health inequities, mpox needs to be taken seriously. However, I think we have a much greater chance of controlling mpox than COVID. For one, mpox is not as transmissible, unless the biology has changed drastically, and that seems unlikely. Secondly, it takes much longer for a mpox infection to develop within an individual and to become transmissible. Therefore, there is a greater opportunity to protect contacts. Third, mpox may not be very transmissible before its visible rash highlights the need for quarantine, while COVID-19 can be transmitted before symptoms emerge and even in asymptomatic cases.

Many cases in the current outbreak have been among men who have sex with men, a focus of the CDC. Do you think these men are at greater risk?

So far, the large majority of mpox cases have been identified in men who have sex with men and this subpopulation is considered to be higher risk for obtaining mpox. The reasons for this epidemiological trend are not fully understood. Recent studies have shown that viral particles are present in semen, but it is unclear whether the disease can be transmitted by semen. Transmission events between sexual partners may be due to prolonged close proximity or skin-to-skin contact of vesicular lesions. However, in the same way that hikers should not be blamed for the persistence of Lyme disease, no one should be blamed for the persistence of mpox because of their sexual practices. In fact, anyone can get mpox and I would be concerned about close contact between any two people when one of them has a rash.

Fortunately, a safe vaccine (JYNNEOS) is available for higher-risk individuals. Vaccination provides individual protection against disease and contributes to the overall control of this outbreak. If you are considered higher risk, please reach out to your primary health care provider or your local public health department to acquire vaccination.

How concerned should we be now about mpox?

On an individual level, the risk of acquiring pox has increased, but it is still lower than many other infections. For those who do get mpox, the disease is often mild. For a serious case such as a painful rash, involvement of the face or co-existing immunosuppression, treatment is available. Treatment requires the use of antiviral medications that are dispensed by a specialized pharmacy since these medications are not yet FDA approved, but often does not require hospitalization.

On a population level, based on the history of mpox over the past few decades and from what we have seen so far, mpox has not reached a level of threat comparable to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. So, while I think we can be cautiously optimistic that the outbreak will be controlled, I think it’s important to have a healthy respect for the potential dangers of any emerging disease and to be ready for the unexpected. We need to support the public health agencies and laboratories that are working hard to understand the epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment options so we are prepared to address whatever circumstances come our way with as much scientific precision as possible.