Millie Hughes-Fulford, the First Woman Scientist in Space, Dies at 75

Millie Hughes-Fulford, PhD, speak with Thomas Lang, PhD, in her San Francisco VA Medical Center laboratory in 2016. Photo by Noah Berger

Millie Hughes-Fulford, PhD, a UC San Francisco scientist who flew in June 1991 aboard the first space shuttle mission dedicated to biomedical studies, died Feb. 2 at the age of 75. She was the first woman to fly as a NASA payload specialist and was part of the first crew to include three women.

On that nine-day mission aboard the space shuttle Columbia, Hughes-Fulford helped complete more than 18 experiments, which included herself and fellow crew members as subjects, as well as rodents and jellyfish. The mission brought back more medical data than any previous NASA mission, including documenting how space flight and microgravity affected the human body, a topic that would remain a focus of Hughes-Fulford’s long scientific career.

After her space flight, she returned to UCSF and became director of the laboratory that bears her name at the San Francisco VA Health Care System, focusing on the impact of microgravity on human cells. She received a NASA award for Best Flight Experiment on STS-131 (launched in April 2010), contributed to over 120 scientific papers, and was a scientific adviser to the Under Secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs for many years. In 2018, she helped found the UC Space Health program, based at UCSF. Ever enthusiastic about science, she continued her work even after she became ill with lymphoma.

The Hughes-Fulford Laboratory at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center has studied the impaired growth of bone cells and immune cells in space, sending multiple experiments on eight separate missions aboard space shuttles and the International Space Station. Understanding the physiological effects of space flight is of critical importance for potential long-term space exploration, such as a Mars mission, and for longer residence in the space station. But space experiments also offer rare opportunities to illuminate the basic cellular mechanisms that affect health on Earth.

“When we go into spaceflight and we have microgravity, we have eliminated one variable. In mathematics, if you get rid of a variable, you can solve the equation, and we’re able to look at the immune system in a whole new way that has not been possible,” said Hughes-Fulford in a 2015 interview.

Her earlier work, beginning on her Columbia flight, focused on space osteoporosis, a continuous loss of calcium and bone due to the loss of mechanical stress in microgravity. Astronauts can lose approximately 1 percent of their bone per month in space. The loss is only partly ameliorated by daily exercise, suggesting that microgravity has additional molecular impacts on how bone cells generate.

NASA’s Lori Meggs at the Marshall Space Flight Center speaks with Millie Hughes-Fulford about her research into fighting the suppression of the human immune system in space. Video by NASA

Hughes-Fulford then turned her research to immunosuppression in space, a phenomenon that had been observed in earlier space flights. On the Apollo missions, for example, half the astronauts reported bacterial or viral infection during their missions or within one week of returning to Earth. Hughes-Fulford’s lab revealed that microgravity altered gene expression and inhibited the activation of T-cells, a type of white blood cell that helps fight off infections. In June 2013, NASA honored that work as a top discovery on the International Space Station. Her most recent immunology experiment flew in January 2015 on a SpaceX mission to the space station.

“Millie launched the careers of many scientists, physicians and surgeons, and space explorers,” said Aenor Sawyer, MD, assistant professor of Orthopaedic Surgery, who co-founded the UC Space Health Program with Hughes-Fulford. “Her legacy will create an impact for many generations to come and her direct scientific contributions will reach far into the future.”

Sawyer said Hughes-Fulford had recently contributed to an upcoming manuscript on the health effects of space travel on women and had collaborated on a immunosenescence project set to launch on SpaceX mission later this year.

Millie launched the careers of many scientists, physicians and surgeons, and space explorers. Her legacy will create an impact for many generations to come and her direct scientific contributions will reach far into the future.

Aenor Sawyer, MD, assistant professor of Orthopaedic Surgery

“She was a person of many virtues, warm, kind and caring, painstakingly honest and straightforward, and possessed of a salty sense of humor,” said Thomas Lang, PhD, professor of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, who was a collaborator and friend.

Millie Elizabeth Hughes was born Dec. 21, 1945, in Mineral Wells, Texas. She entered college at age 16, receiving a degree in Chemistry and Biology from Tarleton State University in 1968 and then a PhD from Texas Women’s University in 1972. She completed a postdoctoral fellowship studying cholesterol metabolism at what is now UT Southwestern School of Medicine in Dallas in the lab of Marvin Siperstein, who later recruited Hughes-Fulford when he moved his lab to the San Francisco VA.

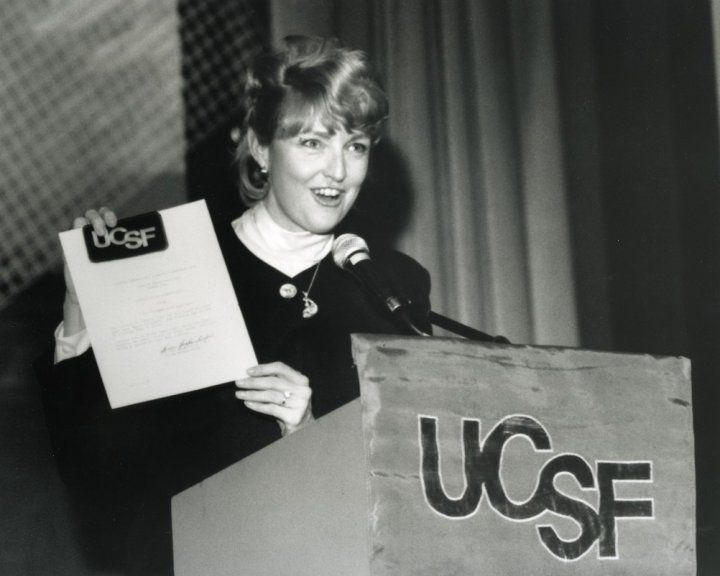

Millie Hughes-Fulford, PhD, speaks at UCSF in the early 1990s. After her space flight in 1991, she returned to UCSF and became director of the laboratory that bears her name at the San Francisco VA Health Care System. Photo via UCSF Archives

A lover of science fiction and a “space buff” from childhood, Hughes-Fulford dreamed of being an astronaut even before space flight became a reality. In 1978, she took a step in realizing that dream by answering an ad in Family Circle magazine seeking candidates to become the first woman in space. Among 8,000 applicants, she made it to the top 20 before Sally Ride was chosen to fly on the Challenger in June 1983.

Although Hughes-Fulford was selected as a payload specialist by NASA in January 1983, the shuttle program was delayed after Challenger exploded shortly after liftoff in 1986. She would realize her childhood dreams five years later on Columbia.

In 1983, she married George Fulford, a United Airline pilot based in San Francisco. She is survived by her daughter Tori Herzog, and granddaughters Shoshana Herzog and Kira Herzog. The family requests that donations in her memory be given to Stand Up to Cancer, P.O. Box 843721, Los Angeles, CA 90084‐3721.