UCSF study finds that an exercise-induced liver protein strengthens the blood-brain barrier, improving memory and slowing age-related decline.

Researchers at UC San Francisco have discovered a mechanism that could explain how exercise improves cognition by shoring up the brain’s protective barrier of blood vessels.

With age, this network of blood vessels — called the blood-brain barrier — gets leaky, letting harmful compounds enter the brain. This causes inflammation, which is associated with cognitive decline and is seen in conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

Six years ago, the team identified a brain-rejuvenating enzyme called GPLD1 that mice produced in their livers when they exercised. But they couldn’t understand how it worked, because it can’t get into the brain.

The new study reveals that GPLD1 works through another protein called TNAP. As the mice age, the cells that form the blood-brain barrier accumulate TNAP, which makes it leaky. But when mice exercise, their livers produce GPLD1. It travels to the vessels that surround the brain and trims TNAP off the cells.

“This discovery shows just how relevant the body is for understanding how the brain declines with age,” said Saul Villeda, PhD, associate director of the UCSF Bakar Aging Research Institute.

Villeda is the senior author of the paper, which was published in Cell on Feb. 18.

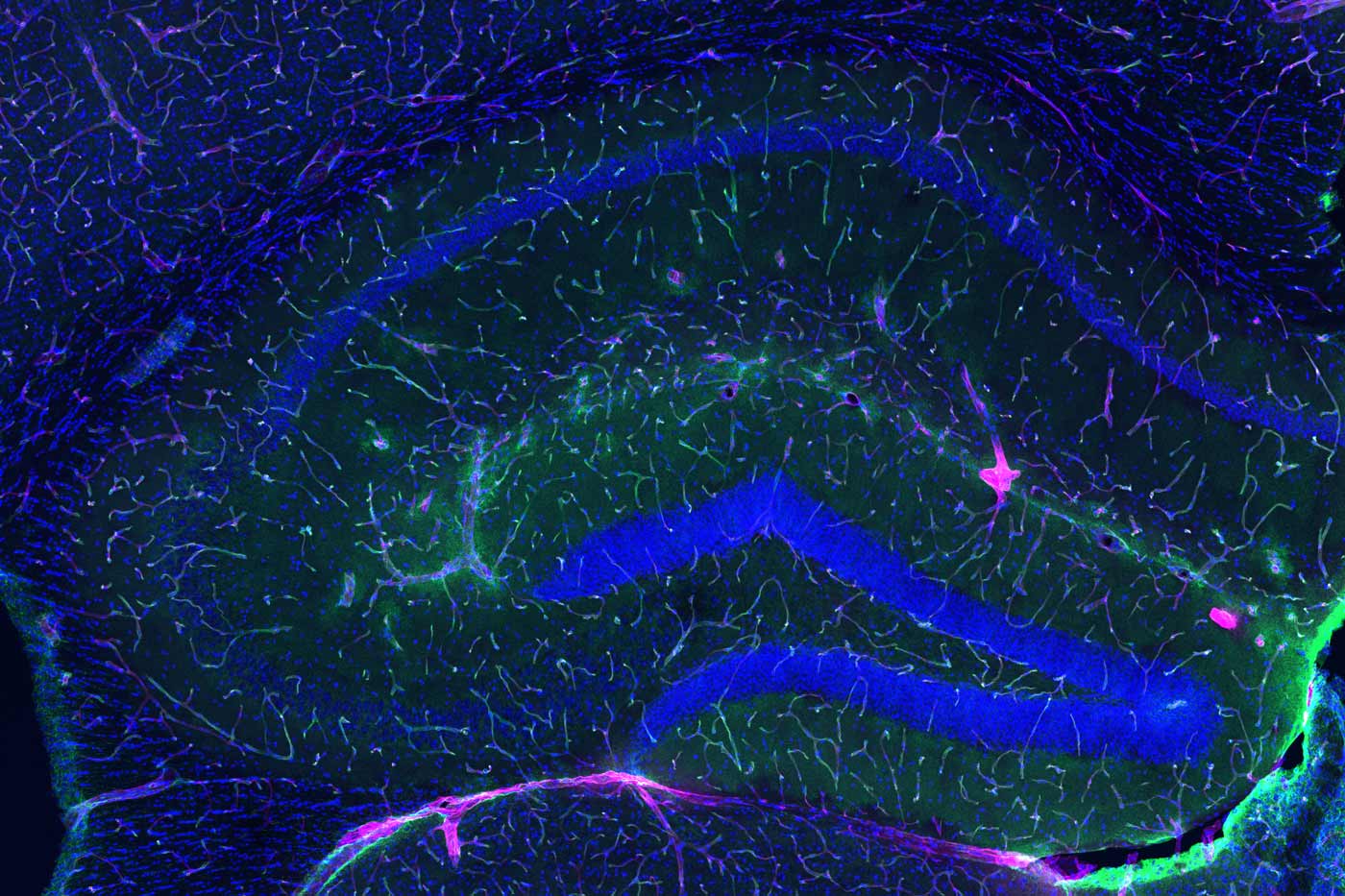

The blood-brain barrier (green line) in a young animal prevents most of an injected dye (pink) from reaching the brain.

Below, the blood-brain barrier in an older animal has degraded and more of the dye makes it into the brain.

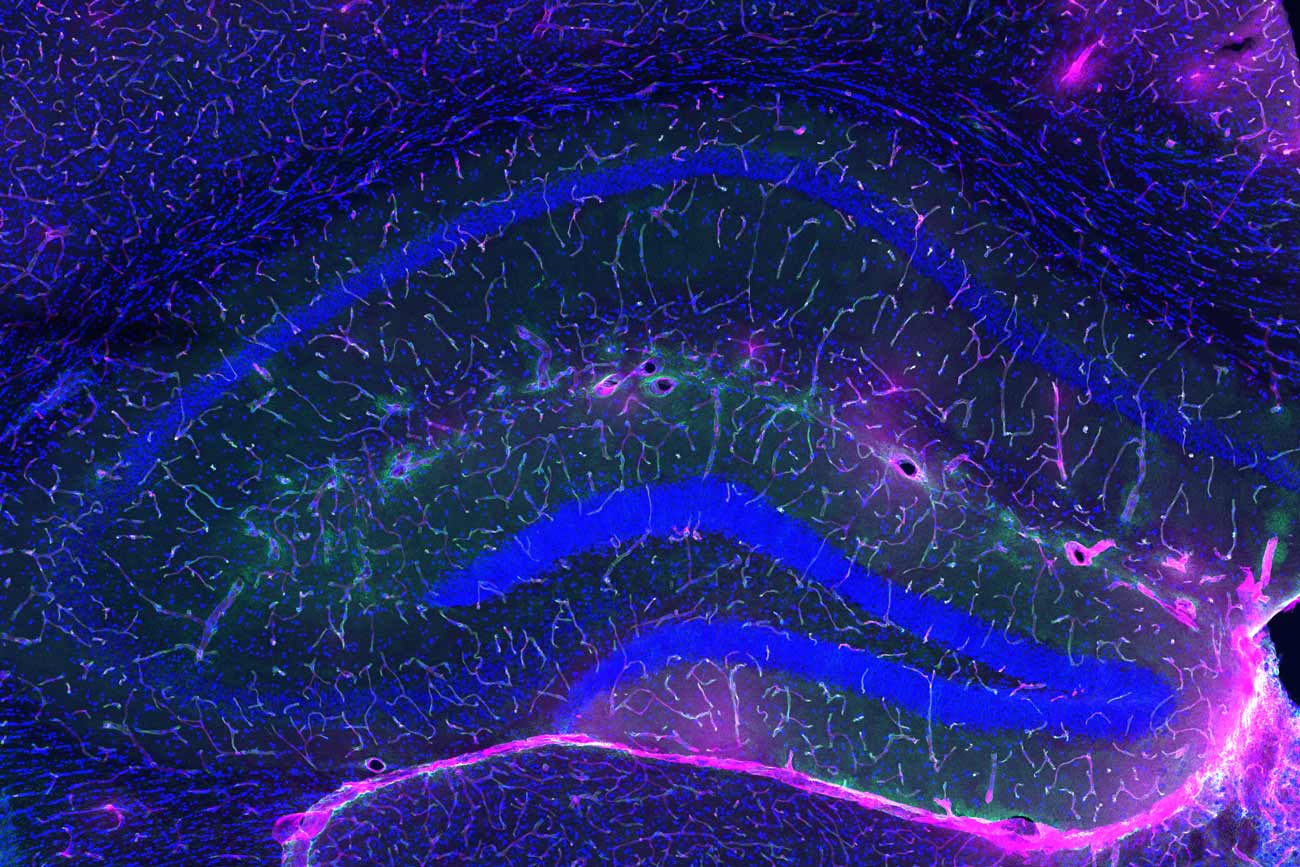

In an old animal treated with GPLD1, the blood-brain barrier rejuvenated and less dye crossed into the brain.

Images Villeda Lab

To begin to understand how GPLD1 works on the brain, the team considered its main job: cutting certain proteins from the surface of cells. Then, they searched for tissues that had proteins on their surface that could be cut by the enzyme. They guessed that some tissues probably accumulated more of these proteins with age.

The cells that make up the blood-brain barrier stood out. They had several GPLD1 targets dotting their surface, but when the researchers exposed each of the targets to GPLD1 in test tubes, it only cut one of them: TNAP.

Young mice engineered to have more TNAP in the blood-brain barrier lost their cognitive abilities as if they were old.

When the researchers used genetic engineering tools to reduce the amount of TNAP in 2-year-old mice — the equivalent of 70 in human years — their blood-brain barrier became less leaky and their brain inflammation went down. The mice also performed better on memory tests.

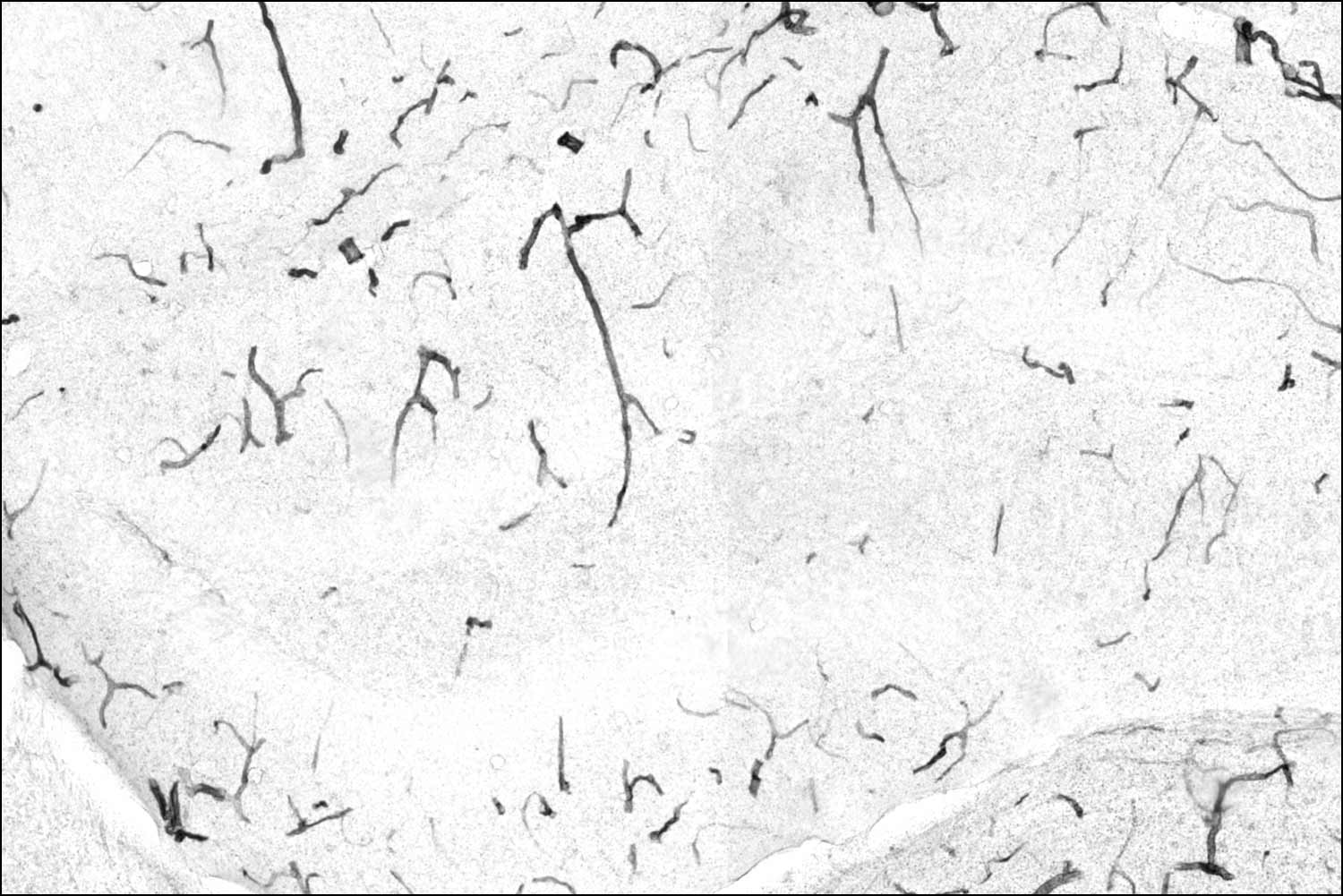

Old animals that are sedentary have lots of TNAP protein (black) on the brain's blood vessels — a hallmark of a degraded blood-brain barrier.

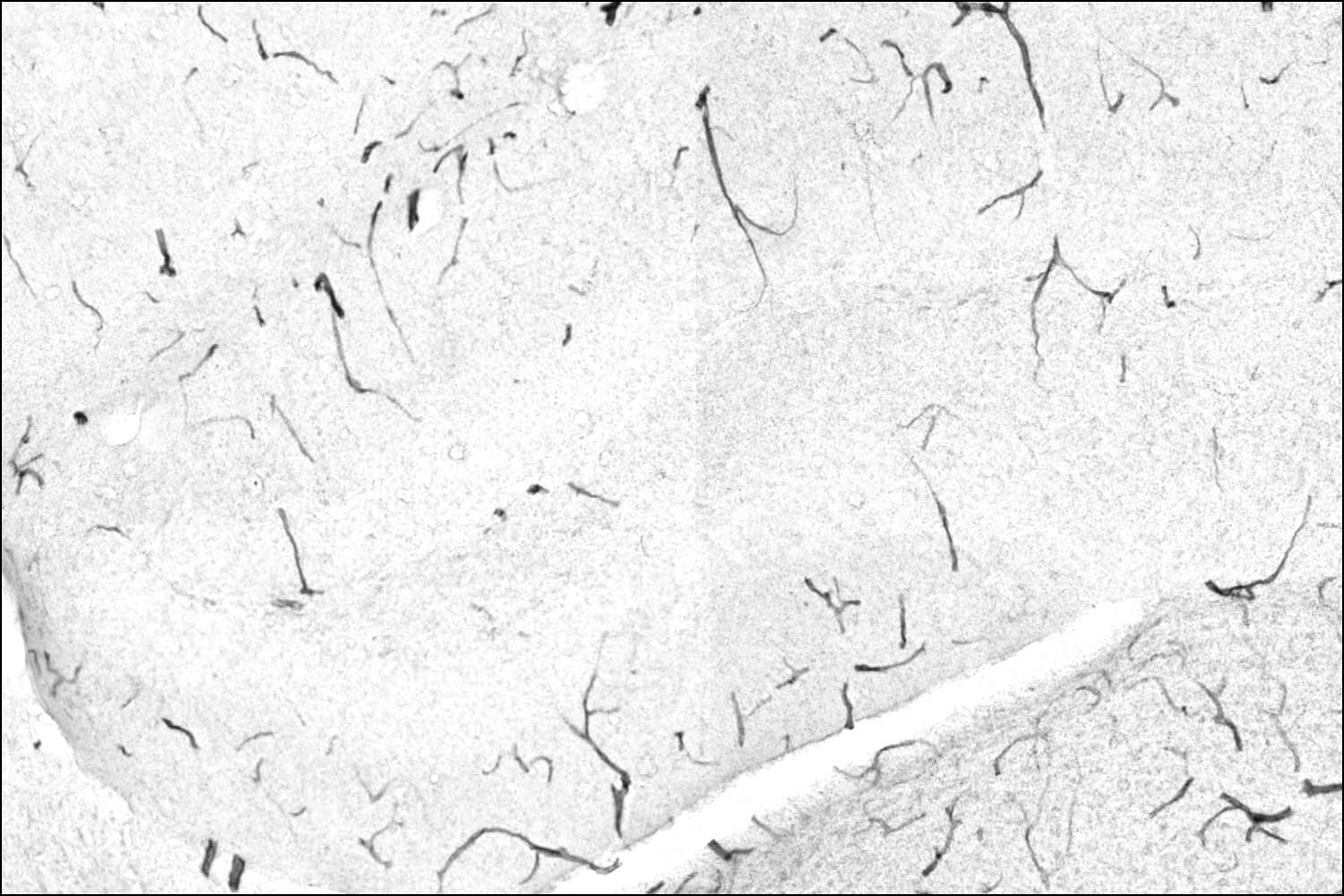

Old animals that exercise have much less TNAP on this tissue thanks to the liver protein GPLD1. Less TNAP means a stronger barrier and a healthier brain.

Images Villeda Lab

“We were able to tap into this mechanism late in life for the mice and it still worked,” said Gregor Bieri, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in Villeda’s lab and co-first author of the study.

Finding drugs to trim proteins like TNAP could be a new way to rejuvenate the blood-brain barrier, even after it’s been degraded by age.

“We’re uncovering biology that Alzheimer’s research has largely overlooked,” Villeda said. “It may open new therapeutic possibilities beyond the traditional strategies that focus almost exclusively on the brain.”

Authors: Other UCSF authors are Gregor Bieri, PhD; Karishma Pratt, PhD; Yasuhiro Fuseya, MD, PhD; Turan Aghayev, MD; Juliana Sucharov; Alana Horowitz, PhD; Amber Philp, PhD; Karla Fonseca-Valencia, degree; Rebecca Chu; Mason Phan; Laura Remesal, PhD; Andrew Yang, PhD; and Kaitlin Casaletto, PhD. For all authors, see the paper.

Funding: The study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (AG081038, AG086042, AG082414, AG077770, AG067740, P30 DK063720); Simons Foundation; Bakar Family Foundation; Cure Alzheimer’s Fund; Hillblom Foundation; Glenn Foundation; JSPS; Japanese Biochemistry Postdoctoral Fellowship; Multiple Sclerosis Foundation; Frontiers in Medical Research; American Federation for Aging Research; National Science Foundation; Bakar Aging Research Institute; Marc and Lynne Benioff.