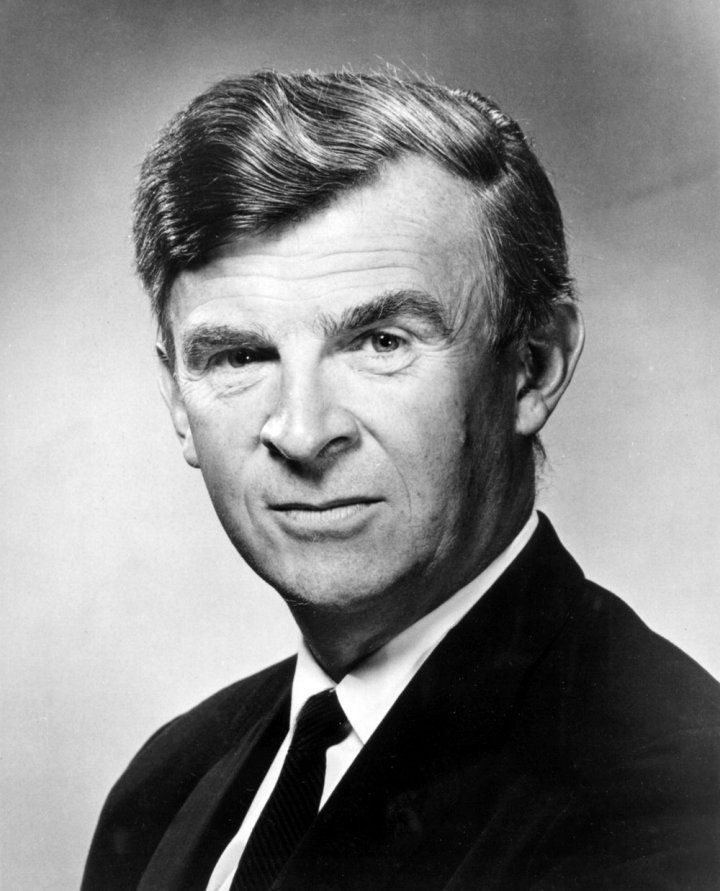

UCSF Remembers Philip Lee, Former Chancellor and Health Care Reformer Who Served 2 US Presidents

Former UCSF Chancellor and Professor Emeritus of Social Medicine Philip Randolph Lee, MD, a visionary leader in health policy research and advocate for social justice, died on Oct. 27 in New York City. He was 96.

During his long career, Lee was a practicing physician, an advocate for racial equity and health care reform, and a greatly admired and inspirational teacher, mentor and administrator.

As the nation’s first Assistant Secretary of Health, in President Lyndon Johnson’s administration, Lee was instrumental in the implementation of Medicare.

He served as UCSF’s third chancellor, from 1969 to 1971, and remained a respected and influential voice among the UCSF faculty until his departure from the University in 1993 to serve for a second time as Assistant Secretary of Health, this time under President Bill Clinton.

“Dr. Lee embodied UCSF’s longstanding commitment to advocating for health equity at the national, state, and regional levels,” said UCSF Chancellor Sam Hawgood, MBBS. “Throughout his life, and during his tenure as chancellor, he was an indefatigable champion for the underserved. We can take inspiration from his example in our continued work to build a more just society, with equal access to quality, affordable health care for all.”

Watch Chancellor Sam Hawgood's tribute to Philip Lee at the 2020 State of the University Address on Oct. 30.

Pioneer of Health Policy Research

As chancellor, Lee presided over the ongoing and steady growth of biomedical research at UCSF while seeking to create a “fifth school” (complementing dentistry, medicine, nursing, and pharmacy) that would integrate health policy, public health, and the social and behavioral sciences. Many of his initial efforts were blocked by then-Governor Ronald Reagan through line-item vetoes. Ultimately, Lee succeeded in launching the Health Policy Program at UCSF in 1972 with a small group of faculty experts in ethics, law, medicine and pharmacology.

Under Lee’s direction, the Health Policy Program grew into an institute – now known as the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies (IHPS) – that increased in research scope and stature. Today, the Institute provides insight for policy implementation through research on a broad range of factors that influence health, health care costs, medical technology, health care providers, and pharmaceutical use.

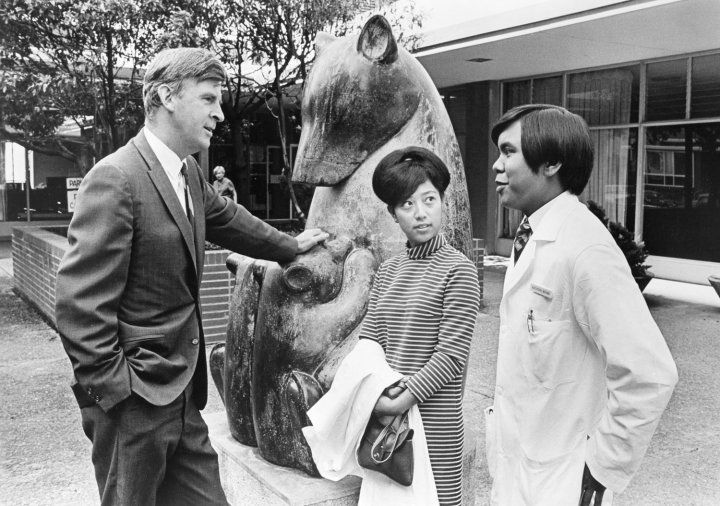

Philip Lee speaking to a pharmacy student on campus in 1968. Photo courtesy of UCSF Archives

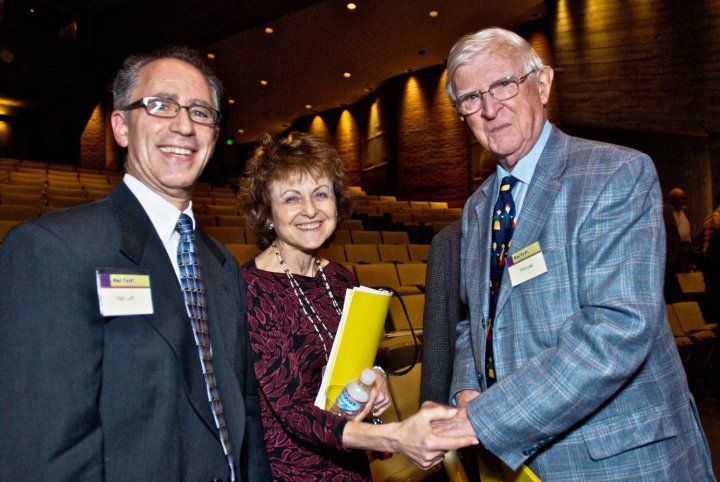

“Phil demonstrated, in small ways and large, how to pivot to meet needs,” said Harold S. “Hal” Luft, PhD, who served as the second IHPS director, from 1993 to 2007, and is now a senior scientist at Sutter Health. “When he began the Health Policy Program, the vision was to offer advice to people in Washington.

"But if Washington stopped being interested in advice, he brought researchers like myself on board to do the work that would provide the answers when questions would again be asked. When HIV/AIDS hit San Francisco, when health reform came back on the agenda, and when pharmaceuticals would be covered under Medicare, the program Phil built had answers ready to be used.”

Claire Brindis, DrPH, joined IHPS in 1983 and went on to serve as its director for 14 years before stepping down in July 2020. She remembers Lee as an inspired leader and caring mentor, and as a pioneer of an interdisciplinary approach to problem solving in research long before that became commonplace in academia.

“The institute he founded became the model for the health policy institutes across the country that are bringing evidence to bear on the decisions that policy makers have to arrive at when faced with limited resources,” Brindis said. “The scaffolding he laid with his ideas endures in all the work of the IHPS today.”

Champion of Diversity and Racial Equity

During protests for equal rights in the late 1960s, Chancellor Lee worked closely with the UCSF Black Caucus, a group of employees who had organized service workers on campus. Lee addressed grievances and demands raised by the Caucus regarding unequal pay and other discriminatory employment practices.

The Black Caucus also advocated for greater racial diversity in UCSF’s professional schools. UCSF had established a goal of 25 percent enrollment of underrepresented groups, and Lee hired an affirmative action coordinator to help increase diversity among UCSF staff, faculty and students.

Lee resigned as chancellor after a relatively short tenure because he felt that political opposition at the state level was hampering his effectiveness in advancing these issues at UCSF. His continued efforts in subsequent years laid the foundation for the myriad initiatives at the University to promote diversity, equity and inclusion that continue to this day.

“To all of us who came under Phil’s spell, his death represents the end of an era,” said Haile Debas, MD, who served as UCSF chancellor from 1997 to 1998. “He was a giant of a leader, a man with passionate commitment to the welfare of the poor and vulnerable, and one who has made important contributions to the national discourse and direction of health policy. I will always remember Phil as the gentle giant who always had time and a smile for everyone and a burning passion to make this world a better place.”

He was a giant of a leader, a man with passionate commitment to the welfare of the poor and vulnerable, and one who has made important contributions to the national discourse and direction of health policy.

Impact on National Health Policy

Born at Stanford Hospital on April 17, 1924, Lee was the third son of Russel Van Arsdale Lee, MD, founder of the Palo Alto Medical Clinic (now the Palo Alto Medical Foundation). He graduated from Stanford School of Medicine and served in the U.S. Navy medical service during the Korean War. He then completed additional postgraduate training before joining his father’s Palo Alto clinic. There, the struggles of his low-income, elderly patients to obtain good, affordable hospital care stimulated Lee’s lifelong interest in shaping policies to reduce health care disparities.

Lee moved to Washington D.C. in 1963 after accepting a position at the U.S. Department of State as director of health services for the Agency for International Development (USAID). He focused on programs to improve malaria eradication, nutrition and health. Lee also framed early U.S. policies for international family planning services.

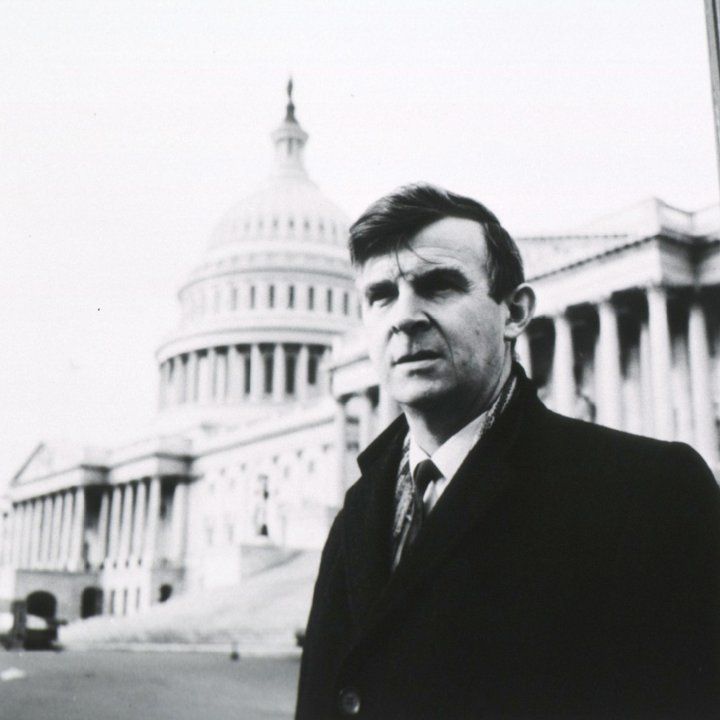

Lee played a leading role in implementing Medicare when he served as Assistant Secretary of Health for the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare (now Health and Human Services) under President Lyndon Johnson from 1965 to 1969.

Philip Lee served under two U.S. presidents, first as Assistant Secretary of Health for the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare (now Health and Human Services) under President Lyndon Johnson from 1965 to 1969. Image courtesy of the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies

The Civil Rights Act was signed into law in 1964, but more than 3,000 of the nation’s hospitals were still practicing racial segregation or other forms of discrimination against patients when the Medicare Law passed the following year. To end these practices, Lee helped design Medicare so that hospitals had to comply with the Civil Rights Act in order to be eligible to receive Medicare payments.

By early 1967, 95 percent of the nation’s hospitals were in compliance, thanks to Lee’s leadership as Assistant Secretary of Health.

“There are few people who have done as much for public health as Phil Lee,” said Lew Butler, JD, who served as associate director in the early days of Lee’s Health Policy Program. “He was instrumental in leading the efforts to incorporate the necessary regulation that resulted in desegregation of hospitals in the South. Phil insisted that if hospitals did not do so, they would not be eligible to receive Medicare and Medicaid funds.”

Lee’s nephew, Peter V. Lee, executive director of Covered California, the state’s health care marketplace under the Affordable Care Act, agreed.

“To Phil, Medicare wasn’t just a ‘big law’ expanding coverage, it was a vehicle to address racial and economic injustice,” said Peter Lee. “With LBJ, Phil used Medicare to desegregate hospitals across America and changed the economic lives of millions of seniors. The COVID-19 pandemic has put a spotlight on racial inequities in healthcare, but this wasn’t new to Phil – he was thinking about these things 60 years ago. The importance of racial equity, health equity, and addressing the social determinants of health are values that Phil embedded in me and in all the people he influenced as a teacher.”

Mayor Dianne Feinstein appointed Lee as the first president of the San Francisco Health Commission, the governing body for the city’s health department. He served in that capacity from 1985 until 1989, during the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. From 1986 through 1993, Lee was chair of Physician Payment Review Commission, charged by Congress to provide advice on reforming physician payments for services to patients covered by Medicare.

Philip Lee with his successive directors of the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies, Hal Luft (left) and Claire Brindis (center). Image courtesy of IHPS

Lee published more than 150 articles and co-authored many books in the health policy field. In 1998, he received the David Rogers Award from the Association of American Medical Colleges. In 2000, he was given the Institute of Medicine’s Gustav O. Lienhard Award for “outstanding national achievement in improving personal health care services in the United States,” as well as the American Public Health Association’s Sedgwick Medal. In 2001, the California Public Health Association presented him with the Henrik Blum Award.

“Phil’s personal achievements in health policy and health are magnified many times over by those of his trainees and mentees who number in the hundreds around the globe. And at his core, it was his personal warmth and caring – the kindness, support and nurturing he provided over generations – that is truly his legacy,” Brindis said.

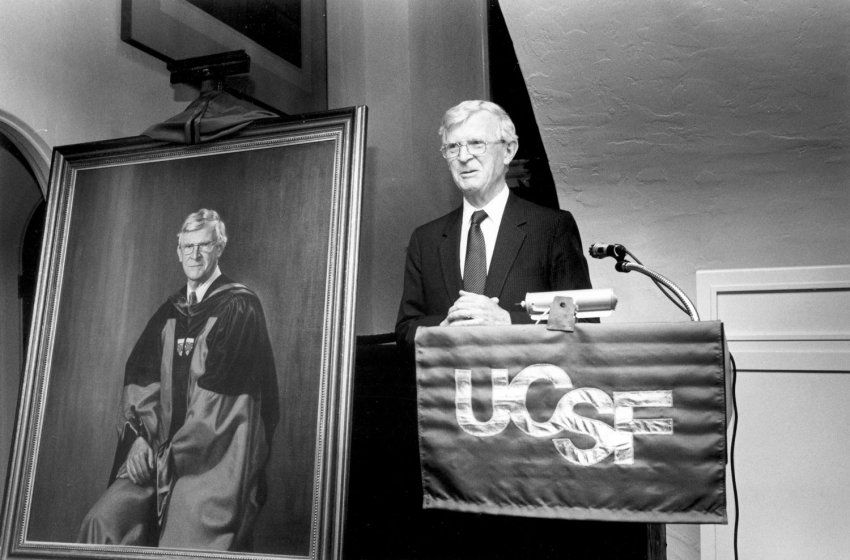

Philip Lee at the unveiling of his official UCSF chancellor portrait. Image courtesy of Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies