Should You Get Tested for Cervical Cancer? Here’s What to Know

Cervical cancer screenings are considered one of the most significant public health advances of the past 50 years, particularly in detecting HPV (human papillomavirus), the culprit of most cervical cancers.

This month, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services updated cervical cancer screening guidelines to include a new option for women at average risk: self-collected HPV tests. The move followed similar recommendations a few weeks earlier by the American Cancer Society.

George F. Sawaya, MD, a UCSF professor of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences and Epidemiology & Biostatistics, is the senior author on a related study that found many women 21-49 years old strongly preferred a self-collected HPV test. He explains the benefits and impacts and why at-home testing was preferred by so many women.

Is cervical cancer preventable?

Cervical cancer is highly preventable through screening. Unlike many other cancers that rely on detection at an early stage, cervical cancer has an identifiable precancerous abnormality that precedes cancer. It takes up to 10 years for these lesions to progress to cancer, giving us a lot of time to identify and treat them. Treatment is highly effective and safe, typically involving a 15-minute office visit.

How does HPV home testing work?

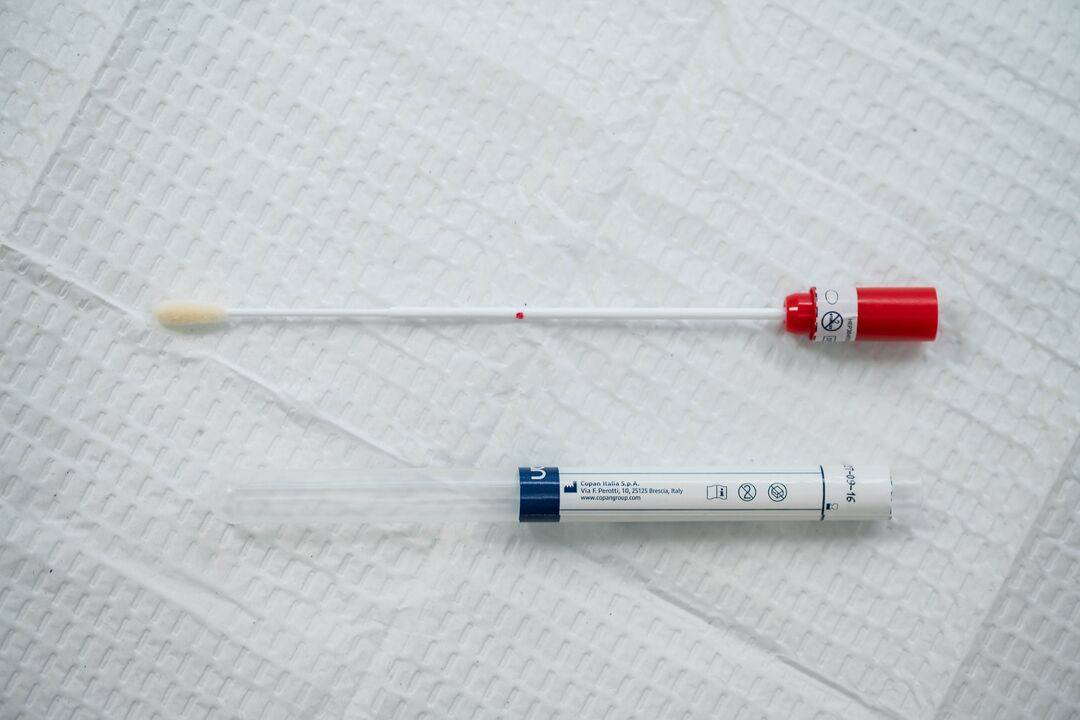

Several different sampling devices have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for collecting vaginal samples to test for HPV, the virus behind nearly all cervical cancers. These samples are collected in either the clinic or at home and are sent to a laboratory. We hope to be able to offer them to UCSF patients soon.

What did your research find?

Last December, we published a nationwide survey with colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and found that about 70% of U.S. women were amenable to self-collected HPV tests. Of course, this also means that about 30% were not, so we need to continue to offer traditional — clinic-based provider-collected — HPV tests. We are moving into an era where patients should be given choices about how they want to be screened.

Which population group most preferred self-collection in your study?

Under-screened and never-screened persons were most likely to prefer self-collection. That’s great news, because most cervical cancer occurs in these populations. The promise of self-collection testing is to increase screening access to persons in these high-risk groups. Most patients will receive normal results, but those who don’t should return for additional testing, a critical step in cancer prevention. Other groups with a stronger preference for self-collected tests include women who described their sexual orientation as not heterosexual and women who reported non-voluntary sexual intercourse.

Why do patients like self-collected tests?

Self-collected HPV tests are designed to give patients more control over screening, allowing them to perform the screening test on their own schedule in a private area of a clinic without a speculum examination or in the privacy of their own home. Studies show that many patients prefer this screening method to the traditional speculum-based specimen collection in a clinic.

What benefits do you see with self-collection?

The major hope with self-collection is that patients who would not otherwise be screened at all will be given the opportunity to participate in the screening program, greatly reducing their risk of developing cervical cancer.

How do you know if you’re at average risk of cervical cancer?

Patients considered to be at higher-than-average risk include immunocompromised persons (such as persons living with HIV), patients with in-utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) — prescribed in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s to prevent complications during pregnancy — and patients with a recent abnormal test or cervical treatment. A clinician should review a patient’s history and determine if self-collection is appropriate.

When should patients begin HPV screening, when should they stop?

The American Cancer Society recommends beginning screening at 25 with HPV tests; other guideline groups recommend Pap tests alone from age 21 to 29 and only beginning HPV testing at 30. Most major medical groups recommend that screening end at 65 in average-risk patients who have had normal tests for 10 years.

What other research is being done at UCSF concerning cervical cancer screening?

We support research programs in Zimbabwe that are exploring whether offering self-collected HPV tests will increase screening in high-risk persons, as well as exploring novel cervical treatments.

With colleagues at Kaiser Permanente, we are determining whether screening should be extended past age 65 by researching the potential benefits, harms, and costs of continued screening. These studies include interviewing older patients about their experiences with being treated for a precancerous lesion over age 65 and exploring the potential for self-collected HPV tests in this population. At Kaiser, we are also participating in studies exploring the efficacy of HPV vaccination in immunocompromised persons with regard to both cervical and anal cancer prevention.