Each year, the National Institutes of Health gives out awards through its Common Fund that recognize exceptionally promising research. This year, UC San Francisco scientists won seven of these prestigious awards.

Their work includes innovative approaches to therapies for cancer and sickle cell disease that harness the body’s innate abilities, a way to map the intricate dance of how proteins regulate genes, optogenetics to see how calcium ions make the heartbeat, a quality-control mechanism for artificial proteins, a search for drugs to heal brain injuries in preterm infants, and a new way to look at the genetics of autism.

Julia Carnevale, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine at UCSF who won an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award.

The last decade has seen incredible advances in fighting cancer with CAR-T therapies, a type of immunotherapy that primes a patient’s own T cells to kill attack their cancer. These engineered T cells are part of the adaptive immune system, which learns from exposure to pathogens, and have been effective in treating blood cancers. But their success in solid tumors has been more limited.

Carnevale envisions harnessing cells from the other part of the immune system, the innate immune system, which quickly responds to anything it senses as foreign — both the adaptive and the innate immune systems to fight against solid tumors. She has developed new tools to reprogram human innate immune cells called myeloid cells to enable them to go after tumor cells — and recruit T cells to help with the fight. By taking advantage of what the body can already do, she hopes to create living medicines from myeloid cells to use in the treatment of solid tumors.

Kyle Cromer, PhD, is an assistant professor of Surgery, and Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences and a member of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regeneration Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCSF who won an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award.

Cromer is working on better treatments for sickle cell disease, which deforms red blood cells, by trying to help the bone marrow produce more healthy red blood cells. This could save patients from having to undergo debilitating high-dose chemotherapy before they can be given new sickle cell treatments that use gene-editing technology. And it could one day mean that the disease is fixed directly in the patient’s body, eliminating the delays and cost of having to correct the malfunctioning blood stem cells in the lab before putting them back into the patient’s bone marrow.

Nicole DelRosso, PhD, is a Sandler Fellow at UCSF who won an NIH Early Independence Award.

Behind all of life is a complex choreography of protein interactions that control a cell’s activity by regulating its genes. To understand this process better, researchers are turning to microfluidics, which can isolate very small amounts of material in tiny droplets. DelRosso has developed a new microfluidic platform that can measure hundreds of interactions between proteins at the same time. Understanding a process so fundamental to life could have far-reaching impacts on both medicine and drug development.

Bill Jia, PhD, is a Sandler Fellow at UCSF who won an NIH Early Independence Award.

Jia is interested in how calcium activity directs the normal development of the heart and contributes to adult heart disease. Because calcium signaling can have many different functions — such as making a muscle cell contract or a pancreatic cell secrete insulin — and it occurs both at the micro (i.e. subcellular) and macro (whole tissue) levels, it’s been hard to study. Jia wants to see how calcium signaling changes in the developing hearts of living embryonic zebrafish, which are easy to observe because they are transparent. He will use optogenetics, a technique that uses light to control cell activity, to manipulate the timing and location of calcium activity in the developing heart. He hopes this will identify the difference between healthy and unhealthy calcium signaling. This knowledge could extend beyond cardiology to benefit neuroscience, immunology, and regenerative medicine.

Tanja Kortemme, PhD, is a professor of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences in the UCSF School of Pharmacy who won an NIH Director’s Pioneer Award.

Nature has evolved many ways to recognize and correct errors when doing something as important as copying DNA or translating it into proteins. Kortemme wants to build similar error correction systems with new AI technology, which synthetic biologists are increasingly using to make artificial proteins. Her protein systems will not be as complex as those found in nature but instead much more programmable. Ultimately, she wants to create diverse off-the-shelf programs that could be used in any human-engineered process that uses both natural and artificial processes. It’s never been done before, but the award will enable Kortemme to work on new ideas in this emerging area of science.

Bridget Ostrem, MD, PhD, is an assistant professor of Neurology at UCSF with expertise in maternal-fetal and pediatric neurology who won an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award.

Ostrem is looking for a way to treat the most common type of brain injury in premature babies: injury to the developing white matter. White matter injury has no current specific treatments, and it can lead to cerebral palsy, cognitive deficits, and seizures, among other lifelong symptoms. Ostrem aims to identify FDA-approved medications that could be repurposed as new treatments for white matter injury in newborns. She will also use an oral antihistamine called clemastine — which was identified by multiple sclerosis researchers at UCSF a decade ago — to spur white matter repair. The award will fund both drug discovery and early-phase clinical trials of preterm babies with white matter injury.

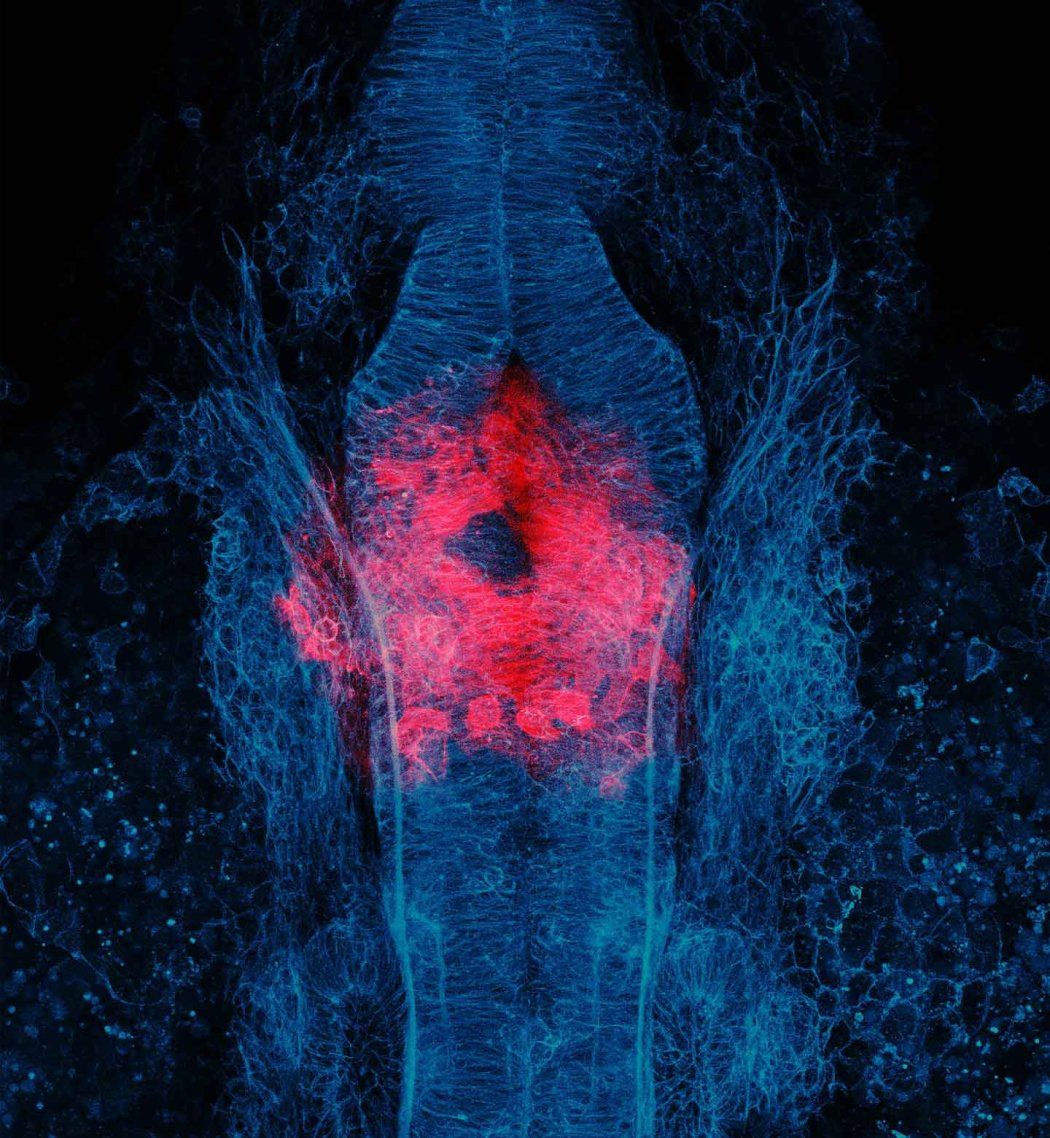

Helen Willsey, PhD, is an assistant professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at UCSF and an investigator with Chan Zuckerberg Biohub San Francisco who won an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award.

Willsey has forged a new path in autism research by looking at how individual genes function at many different levels in brain development. Her work helps focus a field that has been trying to decipher the underlying biology of profound autism by looking at more than 100 genes. She is looking at a subset of these genes that, in addition to helping to package the DNA in a cell’s nucleus, also affect the tiny structures inside cells called microtubules. Variations in these genes may affect both how the brain develops, and how the heart, eyes, and gastrointestinal tract develop. The overlap is promising, since people with profound autism, who require life-long care, are also more likely to have congenital heart disease, along with problems with their vision and digestion.