How COVID-19 Compromised U.S. Gains in Controlling HIV

New data show the country may not reach its goal to eliminate HIV by 2030 as part of federal initiative.

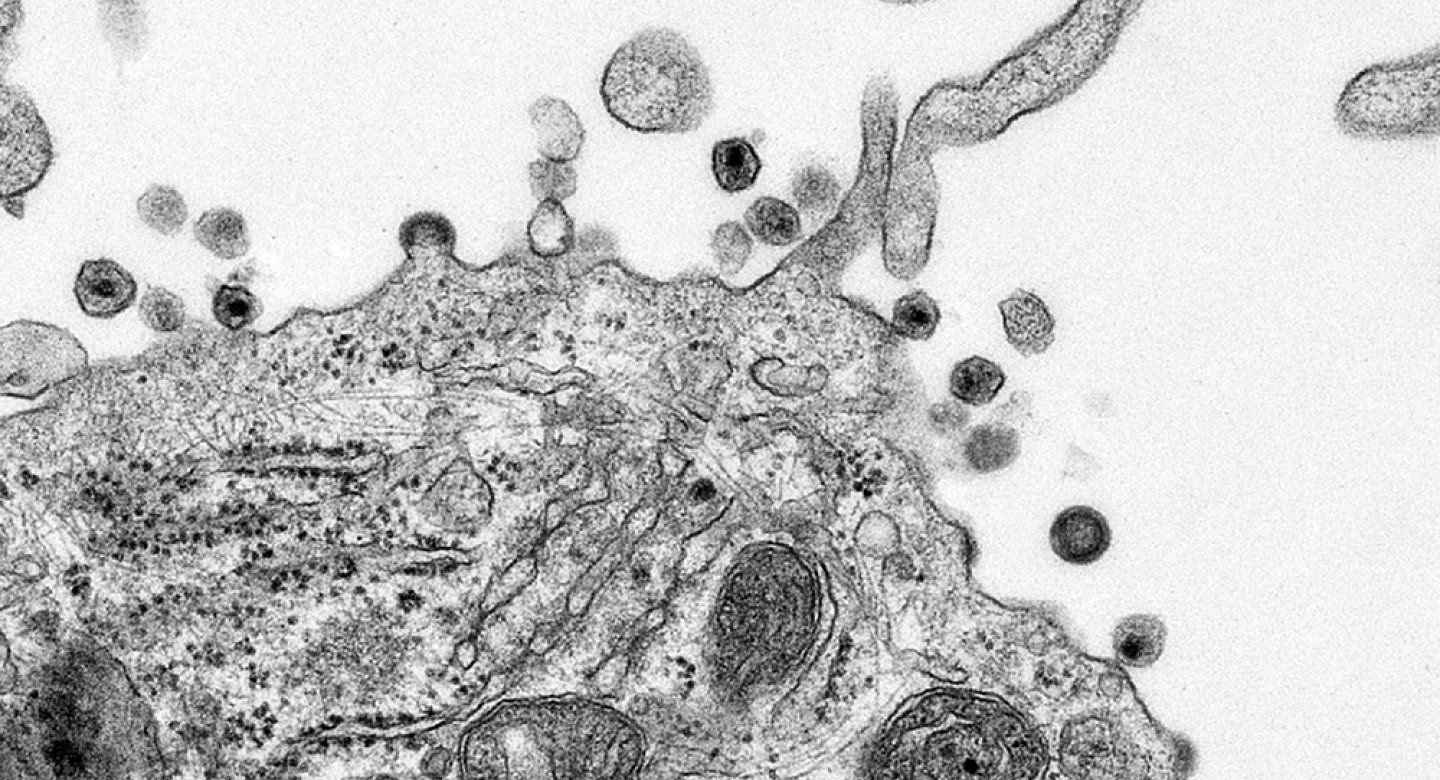

The COVID-19 pandemic slowed previous gains made in controlling HIV blood levels and worsened health disparities, according to UC San Francisco researchers leading the largest U.S. evaluation of the impact of the public health crisis on people with HIV.

While the country had been making progress on its goals to reduce HIV before COVID-19, the researchers found the pandemic compromised those gains by leveling off improvements in the overall population and worsening outcomes among Black patients and people who inject illicit drugs.

“Equity in HIV outcomes likely worsened during the pandemic, with decreased access to necessary care and increased socioeconomic impacts disproportionately affecting these populations,” said the paper’s first author, Matthew Spinelli, MD, assistant professor in the Division of HIV, Infectious Diseases and Global Medicine at UCSF and the Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center.

The study was published Nov. 14, 2023 in Clinical Infectious Diseases, the journal of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

The researchers used data from 17,999 participants from Jan. 1, 2018 to Jan. 1, 2022 at eight large HIV clinics in Baltimore, Birmingham, Boston, Chapel Hill, Cleveland, San Diego, San Francisco and Seattle. They compared results from Jan.1, 2018 to March 21, 2020, tracking outcomes as the pandemic progressed.

We will need to redouble our efforts in responding to the HIV epidemic to regain our momentum, with a focus on improving health equity so that no one is left behind.

Past progress in controlling the virus came to a virtual standstill during the pandemic for the general population. But for certain subsets, mainly Black patients as well as those with a history of injection drug use, the pandemic worsened their outcomes. The percentage of Black patients who kept their viral loads suppressed decreased from 87% to 85%, and for people who inject drugs their level dropped from 84% to 81%.

The shelter-in-place orders around the country limited access to care for patients, especially those who were already experiencing health disparities. Factors included the shift to telemedicine to provide HIV services as well as reduced in-person medical visits. Increased isolation also led to worsening substance use, loneliness and mental health issues for some individuals.

UCSF’s Spinelli said the results show the U.S. may not reach its goals to eliminate HIV by 2030 as part of the federal government’s initiative Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S.

“We will need to redouble our efforts in responding to the HIV epidemic to regain our momentum, with a focus on improving health equity so that no one is left behind,” Spinelli said.

Authors: Additional UCSF co-authors include Katerina A. Christopoulus, MD, MPH, Carlos V. Moreira, MD, Jennifer Jain, PhD, MPH, Nadra Lisha, PhD, David Glidden, PhD, Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, and Mallory Johnson, PhD.

Funding and disclosures: The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grants R01AI158013, R24AI067039 and P30AI027763). Additional funding came from the NIH’s National Institute of Mental Health (P30MH062246) and the NIH’s National Institute on Drug Abuse (U01DA036935 and 1K01DA056306). See study for disclosures.