For years, scientists have known that the anti-aging hormone klotho, infusions of young blood, and exercise each improve brain function in older mice. But they didn’t know why.

Now, two UC San Francisco research teams and a team from the University of Queensland (Australia) have identified platelet factor 4 (PF4) – a small protein released by blood platelets – as a common denominator behind all three.

Platelets are blood cells that normally release PF4 to alert the immune system and clot blood at wounds. The researchers found that PF4 also rejuvenates the old brain and boosts the young brain, potentially opening the door to new therapies that aim to restore brain function, if not tap into a fountain of youth.

“Young blood, klotho, and exercise can somehow tell your brain, “Hey, improve your function,” said Saul Villeda, PhD, associate director of the UCSF Bakar Aging Research Institute and the senior author on the Nature paper. “With PF4, we’re starting to understand the vocabulary behind this rejuvenation.”

Details of the breakthrough appear in a trio of papers in Nature, Nature Aging and Nature Communications published August 16, 2023. Villeda led the study on young blood published in Nature. Dena Dubal, MD, PhD, UCSF professor of neurology and David A. Coulter Endowed Chair in Aging and Neurodegenerative Disease, led the study on klotho published in Nature Aging. Tara Walker, PhD, senior research associate in neuroscience at the University of Queensland, led the study on exercise published in Nature Communications.

They committed to releasing their findings at the same time to make the case for PF4 from three different angles.

“When we realized we had independently and serendipitously found the same thing, our jaws dropped,” Dubal said. “The fact that three separate interventions converged on PF4 truly highlights the validity and reproducibility of this biology.”

Can a 70-year-old brain function as if it’s 40?

In 2014, Villeda found that blood plasma, consisting of blood minus red blood cells, from young mice restored brain function in old animals. His team then found that young plasma contained much more PF4 than old plasma.

Moreover, just injecting PF4 into old animals was about as restorative as young plasma. It calmed down the aged immune system in the body and the brain. Old animals treated with PF4 performed better on a variety of memory and learning tasks.

“PF4 actually causes the immune system to look younger, it’s decreasing all of these active pro-aging immune factors, leading to a brain with less inflammation, more plasticity and eventually more cognition,” Villeda said. “We’re taking 22-month-old mice, equivalent to a human in their 70s, and PF4 is bringing them back to function close to their late 30s, early 40s.”

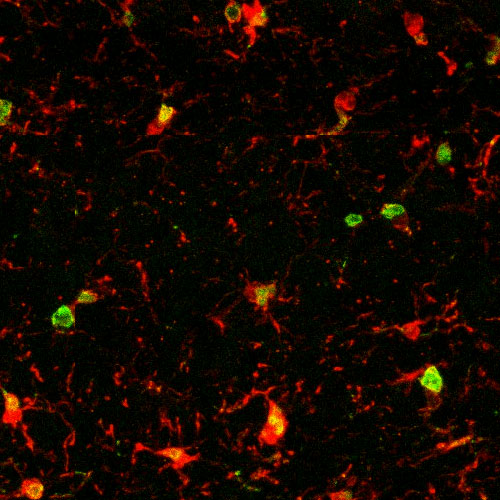

This microscopic image shows microglia, immune cells in the brain, in red. The green and yellow areas point to age-related inflammation in an old mouse.

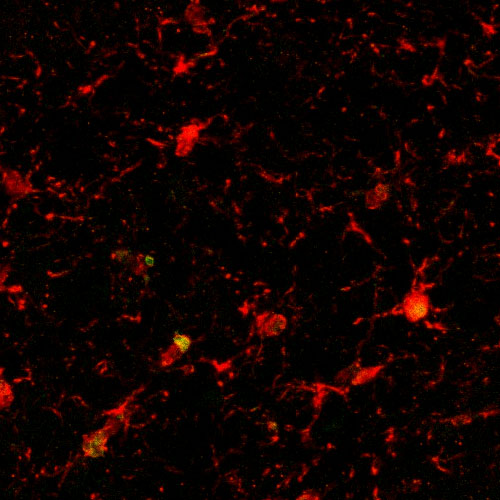

In this image, an old mouse that was treated with PF4 has less brain inflammation. Credit: Adam B. Schroer

Even young brains get a boost

A decade ago, Dubal, a member of the UCSF Weill Institute of Neurosciences, showed that the hormone klotho enhances brain function in young and old animals and also makes the brain more resistant to age-related degeneration. But klotho, injected into the body, never reached the brain. So, how? Dubal’s team found that one connection was PF4, released by platelets after an injection of klotho.

PF4 had a dramatic effect on the hippocampus, where memories are formed in the brain. In particular, PF4 enhanced the formation of new neural connections at the molecular level. It also gave both old and young animals a brain boost in behavioral tests, suggesting that “there’s room to go even in young brains to improve cognitive function,” according to Dubal.

Other recent findings from Dubal have bolstered the prospects for using klotho therapeutically. Klotho’s benefits depend on platelets that release PF4 and other molecules, which could each have their own benefits during aging.

“Ideally, we’ll have multiple shots on goal for one of our biggest biomedical problems, cognitive dysfunction, with the fewest side effects and the most benefit,” Dubal said.

Exercise improves brain health thanks to PF4

Exercise can keep the mind sharp for decades. In 2019, Walker and her lab found that platelets released PF4 into the bloodstream following exercise. When she tested PF4 on its own, like Dubal and Villeda, it improved cognition in old animals.

“For a lot of people with health conditions, mobility issues or advanced in age, exercise isn’t possible, so pharmacological intervention is an important area of research,” Walker said. “We can now target platelets to promote neurogenesis, enhance cognition and counteract age-related cognitive decline.”

Co-authors: Additional UCSF authors on the Nature paper are Adam B. Schroer, PhD, Patrick B. Ventura, PhD, MS, Juliana Sucharov, Rhea Misra, M. K. Kirsten Chui, Gregor Bieri, PhD, Alana M. Horowitz, PhD, Lucas K. Smith, Katriel Encabo, MPH, Imelda Tenggara, June M. Chan, ScD, and Anthony Luke, MD, MPH. Additional UCSF authors on the Nature Aging paper are Cana Park, PhD, Shweta Gupta, PhD, Arturo J. Moreno, Francesca Marino, Dan Wang, MD, MS, Saul Villeda, PhD. Additional UCSF authors on the Nature Communications paper are Adam B. Schroer, PhD, Gregor Bieri, PhD, Saul Villeda, PhD. For all authors, see the papers.

Funding and Disclosures: The research was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (Nature: AG064823, AG081038, AG077816, and AG067740; Nature Aging: NS092918, AG068325; Nature Communications: R01AG077816), as well as through philanthropy. For all funding sources and author disclosures, see the papers.