UCSF Gene Therapy for Deadly Mutation Fast-Tracked for FDA Review

New Designation Could Save Lives Sooner for those with Artemis-SCID

The parents of children born with a rare and deadly condition have new reason for hope, with a new Food and Drug Administration (FDA) fast-track review for a gene therapy developed by researchers at UC San Francisco.

The disease, Artemis-SCID, is a severe form of immunodeficiency caused by mutations in a specific gene. A simple infection can easily kill children with Artemis-SCID in their first year of life if it is left untreated. Even with a bone marrow transplant – the current standard treatment – children with SCID often fail to develop a normal immune system and require repeated infusions to stay alive.

UCSF Pediatrics professors Morton Cowan, MD, and Jennifer Puck, MD, are leading a clinical trial that involves transferring a normal copy of the mutated gene into patients’ own stem cells. The study aims to determine whether the procedure is safe, feasible and results in a normal immune system up to 15 years later.

Early data from the trial are encouraging, Cowan said. “With gene therapy, we are seeing the Artemis-SCID babies we have treated getting older and having normal lives. They have normal T-cell immunity and are getting immunized and vaccinated. You wouldn’t know they had any sort of condition if you met them; it’s very heartening.”

The FDA has now given the treatment a Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy (RMAT) designation, which means the existing research is considered promising and will be expedited for development and review.

“This is great news for the team at UCSF and in particular for the children and families affected by Artemis-SCID,” said Maria T. Millan, MD, president and chief executive officer of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM), which provided a $12 million grant for the trial. “The RMAT designation means that innovative forms of cell and gene therapies like this one may be able to accelerate their route to full approval by the FDA and be available to all the patients who need it.”

Encouraging Early Data

Artemis-SCID affects fewer than 10 children per year in the United States and is far more prevalent in the Navajo and Apache Native Americans than in the population as a whole. It is the most difficult type of SCID to treat with a standard bone marrow transplant (BMT), especially in patients who lack a tissue-matched brother or sister who can donate stem cells.

The new treatment is autologous – created from the stem cells of the affected individual – thus eliminating the most serious risks of BMT that arise from rejection and graft-versus-host disease, in which the donor cells attack the recipient’s tissues. It also does not require high doses of chemotherapy, to which patients with Artemis deficiency are particularly susceptible, making it much safer than a standard transplant.

Artemis-SCID lentiviral gene therapy is an example of “personalized medicine” that would not have been possible without the revolution in the last 10 years in DNA sequencing and greater understanding about how genes work, said Puck, whose research has led to universal newborn screening for SCID, now standard throughout the U.S. and many countries.

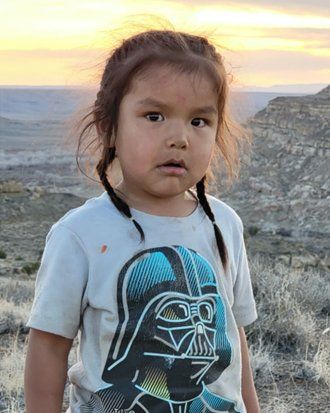

Puck said the first child to receive the new stem cell treatment for Artemis-SCID was born in a remote part of the Navajo Nation.

“He was the first to get this space-age gene therapy,” she said. “And he’s now back on the Navajo Reservation, four years old and running around in cowboy boots.”

He’s now back on the Navajo Reservation, four years old and running around in cowboy boots.

Jennifer Puck, MD