Flu Season Approaches Peak, with Drug-Resistant Cases on the Rise

By Jeffrey Norris

If you are pondering your chances of emerging from the flu season unscathed, these facts won't cheer you. The flu season will soon reach its peak. Nationwide, most flu cases now being reported are due to strains not covered by this year's vaccine, according to the most recent weekly report from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The vaccine contains inactivated strains of two types of influenza A virus, known as H3N2 and H1N1. It also contains one strain of influenza B, a virus that causes a similar but less severe illness. The circulating H1N1 strain is well covered by the vaccine strain. However, neither the vaccine's H3N2 strain nor its B strain match circulating counterparts that now are causing widespread misery.

Furthermore, close to five percent of this year's seasonal flu viruses are resistant to the popular anti-viral drug, Tamiflu.

Lawrence Drew, MD, PhD, director of the clinical virology laboratory at UCSF, notes that resistance to Tamiflu so far is limited to certain cases of H1N1 influenza A infection. Fortunately, that strain of the virus is covered by the vaccine. Even so, for future years, Drew says, "We have to be concerned that resistance to this class of drugs may be an emerging problem." Last year, Tamiflu resistance was very uncommon, occurring in less than one percent of influenza cases.

Drew notes that certain influenza A viruses have recently developed high levels of resistance to an earlier generation of anti-flu drugs, amantidine and rimantidine. Amantadine was used for at least two decades before resistant flu strains emerged, Drew says. The fraction of amantadine-resistant influenza A cases rose from one-in-200 cases during the 1994-1995 flu season to one-in-eight cases during the 2003-2004 season. Two years later, resistance rose so high that the drug was no longer deemed useful. Flu viruses have similarly developed resistance against rimantadine.

These drugs were never active against influenza B, and today the CDC does not recommend either drug to treat influenza A or B infections.

While those earlier-generation drugs targeted only influenza A viruses, the newer Tamiflu, and a similar, but less widely used drug, Relenza, target both influenza A and influenza B viruses.

In an average year, seasonal flu and its complications account for an estimated 36,000 deaths in the US, mostly among the elderly. Drew emphasizes that despite the less-than-optimal coverage offered by this year's flu vaccine, vaccination still is recommended.

"When you are admitted to the hospital, you are a candidate for the vaccine," he says. Hospital physicians routinely receive chart reminders about flu vaccine for patients.

The UCSF clinical virology lab is one of California's "sentinel laboratories." These labs provide data on confirmed influenza and other respiratory viruses. Most of the cases reported by the UCSF lab are detected in UCSF clinic patients or in patients admitted to the hospital. Classifying flu infections as influenza A or influenza B is routine at the sentinel labs. However, tracking drug resistance and individual flu strains is a task generally left to the CDC.

The profile of flu virus identifications reported from the UCSF lab this year - viewable online - more or less mirrors the profiles for the state and nation, as it usually does. What is unusual this year, both locally and nationally, is the large number of influenza B cases, according to Drew. Many patients with influenza B are reporting gastrointestinal symptoms and fevers milder than the typical flu-caused fever.

Seasonal flu incidence charts a remarkably consistent course from year to year. In the United States, flu cases track a bell-shaped curve that in most years peaks in February and lasts an average of 10 weeks, Drew says.

"Type A flu cases are on course to peak by the end of March or early April this year," Drew says. Locally, influenza B is charting a curve that is less bell-like. Even so, Drew says, "It's unlikely that we will see new cases of either flu type after April."

There is another seasonal respiratory illness that hospital physicians are attuned to, but which the general public is little aware of, Drew says. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a threat primarily to infants and immunocompromised patients such as organ transplant recipients. The UCSF clinical virology laboratory reports RSV just as it reports flu. Like flu, it can sometimes lead to life-threatening pneumonia, and like flu, Drew says, "We see it every year at this time of year."

Related Links:

Viral identification at UCSF Clinical Virology Laboratory

The California Influenza Surveillance Project

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Recommended Antiviral Agents for Seasonal Influenza for 2007-2008

UCSF Departments of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

|

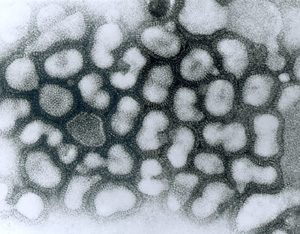

influenza A virus |