Puberty, Obesity, Environment and Breast Cancer

A woman's likelihood of getting breast cancer peaks in her 70s, but some researchers are focusing on puberty to better understand risks. That's because girlhood appears be a window of vulnerability to environmental insults that may result in breast cancer decades later. "Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women, and it may have origins early in life," says Robert Hiatt, MD, PhD, deputy director of the Comprehensive Cancer Center at UCSF. "There may be things that happen during puberty that set the stage for breast cancer later on." Puberty itself looks to be a moving target. A study this month in the journal Pediatrics concluded that girls who are overweight - as early as age 3 - reach puberty earlier on average than normal-weight girls. That's one disturbing trend - childhood obesity - foreshadowing another. In fact, some public health experts are convinced that the average age of puberty, compared with a few decades ago, already has gotten younger by several months. Although this latest news on puberty arrived as a sudden media flash, research on factors influencing puberty gradually has been gaining momentum in recent years. Study Underway to Identify Risks in Young Girls In 2003, Hiatt - along with other investigators from UCSF, Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the advocacy group Zero Breast Cancer - formed a consortium with three other groups led by researchers at the University of Cincinnati, Michigan State University and Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. Researchers at the four Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Centers (BCERCs) agreed on study protocols and set out to study 7- and 8-year-old girls in a seven-year study, funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Cancer Institute. In tandem studies on mice, BCERC scientists are investigating how diet and environmental exposures affect sexual maturation, as well as cellular, biochemical and genetic changes in the developing and mature mammary gland. Window of Vulnerability Everyone has to go through puberty, but when puberty occurs earlier than usual in girls, it increases long-term exposure to estrogen. A longer interval of regular menstrual cycling is associated with a higher relative risk of breast cancer. Hormone levels and breast tissue itself undergo changes throughout the menstrual cycle. A woman whose first full-term pregnancy occurs at age 20 or before has about one-third less breast cancer risk than a woman who does not give birth until after age 30.

|

|

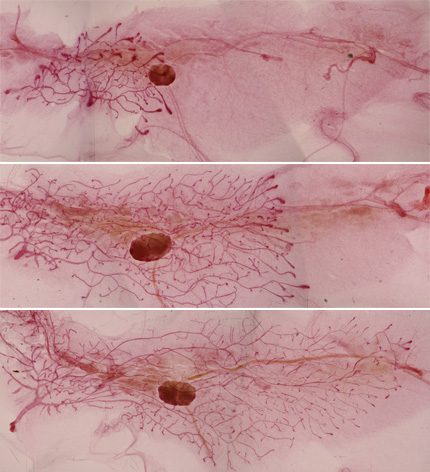

Mouse mammary development at - from top to bottom - 4 , 6, and 10 weeks after birth. Lab researchers are focusing on the period between 4 and 6 weeks - the peak of puberty. At 10 weeks, mice are past puberty. Photo/Marina Burkova, Andrew Ewald, and Zena Werb |

Apart from estrogen exposure, another concern is that girls may be especially sensitive to any harmful effects of chemicals they are exposed to in their daily environments or through diet. Evidence from the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb blasts, from medical records of US girls who received radiation treatments and from animal studies indicates that environmental exposures - at least to ionizing radiation - may have their greatest impact on breast cancer risk before mammary glands have fully developed. The transformation of normal breast tissue into a tumor occurs through steps. Several decades may elapse between the first important change in a cell and the development of an invasively growing tumor. "It could be that during puberty - because it is when the breast is developing and cells are dividing rapidly - DNA is more susceptible to carcinogens," Hiatt says. Even without considering girls' window of vulnerability, females exposed to more cancer-causing chemicals earlier in life might simply be getting a head start on cancer development, Hiatt notes, due to accumulated DNA damage or indirect effects on hormonal metabolism. Engaged Participation At Kaiser Permanente clinics, Bay Area BCERC medical staff and researchers are gathering information annually on height, weight, psychosocial development, lifestyle, diet, insulin sensitivity and environmental exposures, as are collaborators at the other BCERCs. Biological samples are being collected for measurements of genetic variations, hormones, toxicants and other molecular markers.

|

|

Advocates and participant family members attended a Town Hall meeting in San Francisco March 10 to discuss the ongoing study of environmental influences on puberty and breast cancer risk. Photo/Tara Gill for Zero Breast Cancer |

The girls are instructed to keep activity diaries and to use pedometers to measure physical activity. Thanks in part to the recruitment efforts of breast cancer activists, the study quickly exceeded the enrollment goal. Significant numbers of white, African American, Asian and Latina girls are participating - 444 girls in all. At a "town hall" meeting held on March 10 in San Francisco, study researchers discussed early progress and findings with advocates and participant family members. Preliminary Results Preliminary results on weight and stages of pubertal development presented at the town hall meeting mirror those reported in the Pediatrics study and in earlier studies. Fatter girls are more likely to show signs of early breast or pubic hair development. Body mass index - a measure calculated using weight and height - was used to determine that about 45 percent of Latina girls in the study are overweight, along with about 40 percent of African American girls, 30 percent of white girls and 10 percent of Asian girls. Activity levels were associated with body mass index. When it comes to sedentary activities, girls are spending more time watching TV and playing video games than doing homework and reading. If exposures contributing to early puberty are identified through the study, Hiatt says, a policy goal will be to either take steps to eliminate them from the environment or to educate the public on how to reduce exposures. "That would have some salutary effect on risk of breast cancer and perhaps other cancers later in life, as well as on the more immediate negative psychosocial consequences of early puberty," he says. Related Links: Weight Status in Young Girls and the Onset of Puberty

Abstract | Full Text | Full Text (PDF)

Pediatrics 2007;119:E624-E630 Discovering How Environment Contributes to Breast Cancer

UCSF Today, August 21, 2006 Losing Paradise

UCSF Magazine, April 2004 Breast Cancer and the Environment Research

- Weight Status in Young Girls and the Onset of Puberty

- Pediatrics 2007;119:E624-E630

- Discovering How Environment Contributes to Breast Cancer

- UCSF Today, August 21, 2006

- Losing Paradise

- UCSF Magazine, April 2004

- Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Centers

- Zero Breast Cancer

- UCSF Comprehensive Cancer Center