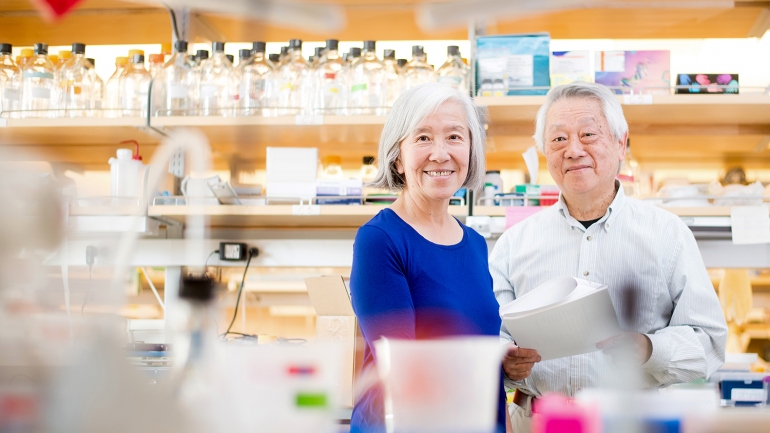

Lily Jan, Yuh-Nung Jan Win 2017 Vilcek Prize Honoring Contributions of Immigrants

Lily Jan, PhD, and Yuh-Nung Jan, PhD, professors of physiology at UC San Francisco, have received the 2017 Vilcek Prize in Biomedical Science, which recognizes extraordinary contributions to biomedical research made by immigrants to America.

Over more than four decades of collaboration, the husband-and-wife team have made numerous discoveries revealing the basic mechanisms of neural development and are leaders in the fields of ion channels and developmental neuroscience.

The Best Possible Place to Do Science

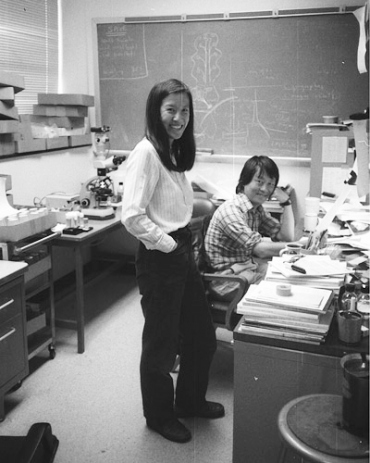

The Jans emigrated from Taiwan in 1968 to attend graduate school at the California Institute of Technology, and they joined the UCSF faculty in 1979.

“We came here as graduate students, we were permanent residents for quite a number of years, and now we are citizens,” said Lily Jan, the Jack and De Loris Lange Endowed Chair of Physiology and Biophysics.

“All this time, this country felt like the best possible place for us to do science and a major part of that is it’s so open,” she said. “People could be from any country and we see them and interact with them as scientists, as part of the community.”

Yuh-Nung Jan, the Jack and De Loris Lange Endowed Chair of Molecular Physiology, noted that immigrants have long played an important role in science in the U.S., including their PhD adviser at Caltech, the Nobel Prize laureate Max Delbrück, who inspired them to switch from physics to biology. Delbrück was an immigrant who escaped Nazi Germany.

“It’s a two-way street,” said Yuh-Nung Jan. “Immigrants contribute a great deal to U.S. science, and conversely, if we were not working in the U.S. it would not be possible for many of us to do what we do here.”

Breakthroughs in Developmental Neuroscience

The Jan’s achievements as researchers have been foundational to the field of developmental neuroscience.

Through experiments in the fruit fly nervous system, the Jans have identified evolutionarily conserved genetic programs that guide the steps of neural development, from the birth of neurons, to their differentiation into diverse cell types, to their assembly into complex neuronal circuits.

Their discoveries include the gene atonal, which initiates the development of two major types of sensory neurons used in vision and hearing; and the gene numb, which is involved in asymmetric cell divisions that give rise to cells of different fates.

They have also been pioneers in the study of potassium channels, which control the flow of electrical signals in the brain and nervous system and are implicated in conditions ranging from epilepsy to hypertension. When the Jans began to study them, potassium channels could only be detected indirectly through their electrical effects. In 1987, after nearly a decade of work, they were the first to clone a gene, known as Shaker, that encoded a potassium channel.

Earlier work by the Jans, when they were postdocs at Harvard Medical School, proved that peptides could act not only as hormones but also as neurotransmitters that regulate the activity of neurons.

More recent work in the Jan lab has focused on the morphogenesis of dendrites, and the physiological function of potassium channels, calcium-activated chloride channels and mechanosensitive ion channels.

The Award and Current Affairs

“We feel very much humbled and honored by this award,” said Lily, but added that at the same time they were deeply troubled by the recent events surrounding immigration.

Last week, President Donald Trump signed an executive order that restricts people from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States.

That order, the Jans said, could reduce the draw of the United States for top scientists around the world. “Up to last week, we’d never experienced anything like this at all,” Lily Jan said. “That’s part of the reason why it’s so upsetting. The attraction, the standing and the reputation of a country can be easily destroyed.”