UCSF Leads Bay Area in Lower-Risk, Lower-Cost Heart Procedure

The cath lab team at UCSF Heart and Vascular Center monitor the progress of Dan Gulley’s heart catheterization procedure.

Dan Gulley waits patiently in a hospital bed at UCSF Medical Center at the Parnassus campus early Friday morning. He is here for a heart procedure to take care of a 90 percentage blockage in one of his coronary arteries.

The retired, 75-year-old former FBI employee is not worried, though. His doctor will perform a lower-risk cardiac procedure that goes through the radial artery in his arm, an uncommon practice in this country. More than 95 percent of heart catheterizations in the U.S. are performed through the femoral artery in the patient’s leg. Only one to five percent are performed through the radial artery.

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) performed radially is not only a lower-risk alternative, it is also lower-cost, since some patients can go home the same day. On average, the cost for UCSF patients who had a radial approach PCI were 28.5 percent lower than those who had a PCI using a femoral approach. Typically, PCI’s performed through the patient’s femoral artery require patients to stay overnight for observations, which requires more medical resources.

“It’s pretty amazing if you think about it, compared to the old way where they had to do the procedure by cracking open a chest,” Gulley said. “So this is the same result but much easier.”

Leading the Bay

UCSF leads the Bay Area in radial catheterization innovation. In 2006, only 2 percent of cardiac catheterizations were performed though the radial artery. Last year, it was more than 30 percent; this year it will be well over the 50 percent mark. UCSF is actively involved in studying new methods to improve radial artery catheterizations, hoping that more cardiologists nationwide will adopt the radial artery approach.

Andrew Boyle, MBBS, PhD

“In the beginning I was using equipment made for the leg so I went out and bought all the proper guide catheters designed for the arm and I worked my way through,” said Andrew Boyle, MBBS, PhD, an interventional cardiologist with the UCSF Heart and Vascular Center. “We use smaller catheters now and technological advancements have allowed us to increase the size of the artery by 24 percent. All these incremental steps have made radial much more doable.”

Cardiac catheterization started as a surgical procedure in the 1930s that required a “cut down” method — called the Sones approach — in which surgeons removed soft tissues in the patient’s arm until they saw the brachial artery, which was punctured by a catheter. Surgeons then sutured the artery, and stitched the arm back together.

In 1953, Swedish radiologist Ivar Seldinger developed a percutaneous approach, in which access to the artery is performed through a needle puncture instead of cutting into the flesh to expose the artery. Since the leg’s femoral artery is large and easily accessible, the percutaneous approach quickly became the standard for more than 30 years.

The Latest Breakthrough

Radial catheterization signals the latest milestone in treatment of coronary artery disease. It has been adopted as the overwhelming standard in places like Norway, Japan and Canada, with implementation rate as high as 90 percent. However, some countries like Australia and the U.S. are slower to adopt, with saturation as low as 4.2 percent, according to the Cardiovascular Roundtable Research and Analysis.

“The radial method is a better approach,” said Boyle. “It has less bleeding, less damage to the artery you’re going in, less requirement for blood transfusions, and less requirement for surgery to repair the damage to the artery.”

Fewer Complications

Patients who underwent radial interventions had a significantly lower rate of major vascular complications and mortality — about two-thirds less — compared to those receiving cardiac catheterization through the femoral artery, according to the Cardiovascular Roundtable Research and Analysis. Locally, Boyle has had only two complications out of more than a thousand radial procedures performed.

“The problem with the femoral artery is that bleeding is sometimes deep,” said Boyle. “So it’s called a retroperitoneal bleed or an RP bleed and that’s lethal. And everybody’s had patients who have died from it. The catheter went fine and the procedure went fine, but they bled and they bled deep and no one knew until they went into cardiac arrest and they were dead. That’s rare but it happens.”

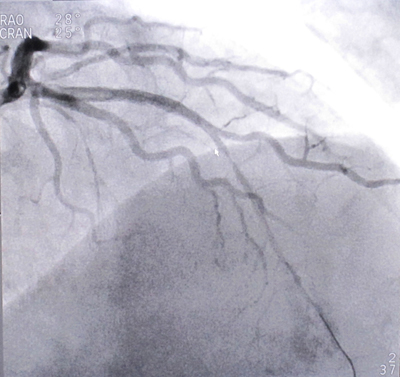

An image of patient Dan Gulley’s heart, which shows a 90 percent blockage to one of his coronary arteries.

And obese patients can have unforeseen complications if the femoral approach is used because of extra layers of fat in their thigh. If they have bleeding under the skin, it can go undetected until they lose up to half of their blood volume. Often they need transfusions and sometimes even surgery to fix the problem.

And there’s a complication called pseudoaneurysm, which is a localized collection of blood outside the blood vessel that forms from a leaking hole in an artery.

“In the wrist, we just put a pressure bandage on,” said Boyle. “In the groin, they usually need surgery. They're in the operating room and it’s a huge cost. Now they have a wound with a drain tube in. That means another two days in the hospital.”

Preferred by Patients

And patients seem to prefer the radial method because recovery time is greatly reduced. In the typical femoral method, patients have to lie flat on their back between three and eight hours after the procedure. And 99 percent have to stay overnight at the hospital.

Because Gulley’s blockage was cleared using the radial method, the entire procedure lasted less than an hour and he got to go home a few hours after that, in time for dinner.

“It was a piece of cake,” he said. “I’ve been through this a couple of time before and I’ve had more discomfort having my teeth cleaned compared to this. It’s very simple and very nice.”

Another advantage is that patients do not have to fast during the recovery period, which means Gulley can eat lunch, something that is not always possible with the femoral approach.

“Eating is very important to me,” he said. “So the new method is a vast improvement over the old one.”

Leading the Way

Radial cardiac catheterizations have become the norm at UCSF. Its interventional faculty have integrated this approach into their practice much quicker than other cardiovascular programs, and Boyle believes the radial method will catch on with the rest of the country.

“It’s the last resort for some but it should be the other way around,” he said. “There’s a huge shift. There’s a big groundswell towards doing radial cases, and there are lots of courses now. So it’s coming.”

For Gulley, the future is now.

“It’s wonderful for my peace of mind,” he said. “Dr. Boyle’s the best in the business as far as I’m concerned. And he explains everything and tells you exactly what he’s going to do, and how he’s going to do it.”

“I feel great and I can’t ask for anything more than that.”

Photos by Leland Kim (except portrait)