Mobile App With Activity Tracker Promotes Physical Activity in Women

App Shows Sustained Benefit for Additional 6 Months, UCSF Researchers Find

A mobile phone app designed to promote physical activity, combined with an activity tracker and brief personal counseling, was effective in encouraging women to exercise for three months and to continue their activity for six more months after their app use ended, according to a study by researchers at UC San Francisco.

Once individuals mastered skills and knowledge during the initial intervention, they only needed the accelerometer to continue, not the mobile app, said the researchers in their study online May 24, 2019, in JAMA Network Open.

Yoshimi Fukuoka, RN, PhD, lead author.

“Studies show that engaging in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week can reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes and certain types of cancer,” said lead author Yoshimi Fukuoka, RN, PhD, professor in the UCSF School of Nursing. “Digital technologies are moving faster than research in transforming the way we promote physical activity and in reducing risks of chronic illness. But, in addition to an activity tracker and mobile app, having activity goals, self-monitoring and accountability are important.”

Despite numerous health benefits, most American adults are not physically active in accordance with the second edition of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2018), and women across all age groups are less likely to be active than men.

Mobile phone apps and activity trackers have become increasingly popular and may be cost-effective for promoting activity, while allowing researchers to remotely deliver an intervention and monitor resulting effects. However, previous interventional studies have been frequently short, sample sizes small, and use data or user engagement information seldom reported.

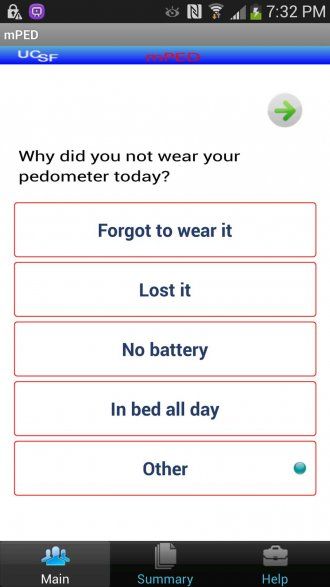

An example question prompted by the app. Credit: Yoshimi Fukuoka.

In the JAMA Network Open study, Fukuoka and her colleagues examined whether a mobile phone physical activity app combined with brief, in-person counseling increased and maintained levels of physical activity. They developed a mobile app featuring a daily message or video clip that reinforced the seven domains addressed during counseling, along with a daily diary for recording progress. The app also included “summary,” “help,” “talk to us” and “weekly goals” options. Activity goals were automatically increased by 20 percent each week to a daily goal of 10,000 steps.

The researchers recruited 210 physically inactive women, as determined by completion of a Stanford Brief Active Survey, who were equally randomized into control, regular and plus groups, and collected data from May 2011 to March 2015. The regular and plus groups used the mobile phone app and accelerometer daily for three months, along with the brief counseling. For six months after that period, the plus group continued app and tracker use, while the regular group used the tracker only. The control group used the tracker only throughout the entire nine-month study period and did not receive any intervention.

The accelerometer was programmed to collect physical activity intensity every 60 seconds daily for nine months, as well as the number of steps and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA). The daily message or video clip was sent between 11 a.m. and 3 p.m., with the diary accessible from 7 p.m. to midnight. If a diary entry was not made by 8:30 p.m., an automated text message reminded the participant to record total daily steps, as well as the type and duration of physical activities. Participants also received an automated message if they did not use the app for three consecutive days.

With a 97.6 percent retention rate after nine months, the researchers found that the three-month intervention with the mobile app and brief counseling resulted in a net increase of 2,060 steps daily for the regular and plus groups (equivalent to a mile or 20 minutes of walking) and 18 more minutes of MVPA per day than the control group, as calculated by the accelerometer.

In the subsequent six months, the average daily steps in the regular and plus groups were about 1,360 higher, along with slightly more minutes of MVPA, compared to controls. But, the progressive step and MVPA increases in both groups declined at similar rates, demonstrating that continued app use by the plus group did not show additional benefits over the accelerometer alone in maintaining the initial increase in physical activity.

According to the researchers, the intervention may have been effective initially because the app and brief counseling were tailored to targeted women and utilized established effective behavioral change strategies, such as goal setting, self-monitoring and automated reminders.

The intervention effect did not differ by age, annual household income, education, race and ethnicity, or body mass index. However, the findings may not be generalizable to men.

The researchers said the next step is to utilize artificial intelligence (AI) approaches, such as machine learning and natural language processing (NLP), to physical activity programs. They already have developed a model predicting activity relapse based on the incoming activity data and other factors, as well as pilot trials that show machine learning-based automated personalized goals were more effective than a fixed 10,000 steps per day goal after seven weeks. They also applied NLP to understand women’s motivational profiles to be physically active.

“AI has great potential to provide personalized physical activity and lifestyle modification programs and efficiently allocate resources to individuals needing the most assistance,” Fukuoka said. “We plan to conduct a randomized controlled trial that examines the effect of the AI-based physical activity intervention in those with cardiovascular risk factors.”

Co-Authors: Senior author Eric Vittinghoff and Feng Lin, of UCSF; and William Haskell, of Stanford University

Funding: Financial support was provided by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant R01HL104147 and the American Heart Association.

Disclosures: Fukuoka reports grants from the National Institutes of Health and American Heart Association during the study.

UC San Francisco (UCSF) is a leading university dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. It includes top-ranked graduate schools of dentistry, medicine, nursing and pharmacy; a graduate division with nationally renowned programs in basic, biomedical, translational and population sciences; and a preeminent biomedical research enterprise. It also includes UCSF Health, which comprises three top-ranked hospitals – UCSF Medical Center and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospitals in San Francisco and Oakland – as well as Langley Porter Psychiatric Hospital and Clinics, UCSF Benioff Children’s Physicians and the UCSF Faculty Practice. UCSF Health has affiliations with hospitals and health organizations throughout the Bay Area. UCSF faculty also provide all physician care at the public Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center, and the SF VA Medical Center. The UCSF Fresno Medical Education Program is a major branch of the University of California, San Francisco’s School of Medicine.