Gut Feeling for Probiotics Benefits May Be Overstated, UCSF Study Shows

Supplement Had No Apparent Effect on Children at High Risk for Eczema, Asthma

The protective effects of probiotics against colds, tummy bugs and more serious conditions have been exalted – and contested. Now a new study headed by UC San Francisco researchers further fuels the probiotics debate by finding that there is no clear evidence that a supplement of the “friendly” bacteria strain of lactobacillus prevents eczema, a frequent precursor to asthma.

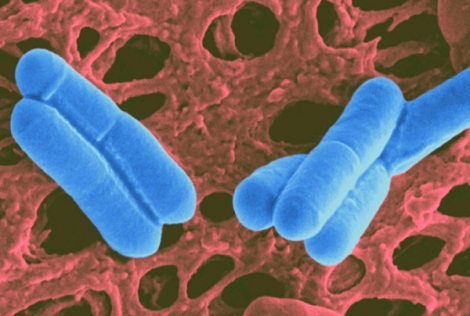

Probiotics, sold as dietary supplements and found in yogurt, kefir and fermented foods, are believed to enhance the defensive action of the cells that line the gut by stimulating healthy immune function and by inhibiting the growth of viral and bacterial pathogens. They are described by the World Health Organization as “live micro-organisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host.”

In the study, which publishes in the journal Pediatrics and is available online on Aug. 7, 2017, the researchers compared the impact of the probiotic among children who had received it for the first six months of life, with those who had not. All infants were at high risk of developing asthma, due to one or both parents having the condition, which is caused by both hereditary and environmental factors.

Infectious Exposure May Impact Asthma

Exactly half of the 184 newborns received capsules of the probiotic. The second group of 92 newborns received placebo capsules with the same look and feel as the probiotic.

The goal was to see if the probiotic would lessen the risk of eczema and asthma.

“Environmental factors during early infancy can affect immune system development and risk for allergic disease,” said first author Michael Cabana, MD, director of the division of general pediatrics at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital San Francisco.

“One theory is that the absence of infectious exposure at a critical point in immune system development leads to a greater risk for eczema and asthma. Additionally, lack of key bacteria in the infant intestinal microbiota has been associated with the later increased risk of allergic disease. Supplementing with specific probiotic strains may modify the entire microbiota community patterns and decrease this risk,” he said.

But the researchers found little difference between the two groups: at age 2, 30.9 percent of the placebo recipients were diagnosed with eczema, versus 28.7 percent of the probiotic group.

Eczema incidence is significant because it frequently precedes asthma.

Eczema May Be ‘First Step’ to Asthma

“It is believed that there is a biological pathway with eczema as a first step in a progression that may lead to asthma,” said co-senior author Homer Boushey, MD, of the UCSF Department of Medicine. In the study, 18 of the 27 children with eczema (67 percent) developed asthma over an average follow-up of 4.6 years.

While fewer 5-year-olds diagnosed with asthma were in the probiotic group, just 27 patients in total received the diagnosis, a number that was too low, at present, to make any findings clinically meaningful, said Cabana, who is also with the UCSF Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, and the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies. “We will continue to learn more with follow-up as more children reach 5 years of age.”

Boushey noted that research by other scientists had determined that there were significantly fewer microbes in the stool samples of infants that later developed asthma. “There is a growing body of evidence that suggests differences in microbial exposure and in intestinal microbes in early infancy are related to differences in the development of immune function, and thus in the risk for developing allergies and asthma,” he said.

“What we don’t know yet is which bacteria are most beneficial, what they produce that mediates the benefit and how best to introduce them to babies. What our study shows is the feasibility of introducing one potentially beneficial microbe. This is just an early step on what will likely prove a long journey.”

The study follows Cabana’s editorial, published in the August issue of Pediatrics and co-written with Daniel Merenstein, MD, of Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, D.C. The authors commented on a study published in the same issue that found probiotics did not impact absenteeism among healthy infants in a child-care center.

Incidence of Breastfeeding, a Possible Factor

The infants in the study had a high rate of breastfeeding, similar to the participants in the UCSF Study – at age 1, 51 percent of the probiotic recipients and 45 percent of the placebo recipients were breastfeeding.

“Because of the large percentage of breastfeeding in both studies, it may be difficult to detect the protective effects of probiotics. Their impact may be overshadowed by the known protective effects of breastfeeding,” said Cabana.

“Breast milk contains natural compounds that act like prebiotics, promoting the growth of specific bacteria in an infant’s gastrointestinal tract. Overall, the best source of influencing your child’s gastrointestinal tract is breast milk, not a probiotic supplement.”

The study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Clinical and Translational Science Institute at UCSF.

The other researchers were co-senior author Joan Hilton, ScD, of the UCSF Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics; and co-authors Michelle McKean, RD, Lawrence Fong, MD, and Susan Lynch, PhD, also of UCSF; Aaron Caughey, MD, PhD, of the University of Oregon Health Sciences in Portland; Angela Wong, MD, of Kaiser Permanente in San Francisco; and Russell Leong, MD, of California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco.

UC San Francisco (UCSF) is a leading university dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. It includes top-ranked graduate schools of dentistry, medicine, nursing and pharmacy; a graduate division with nationally renowned programs in basic, biomedical, translational and population sciences; and a preeminent biomedical research enterprise. It also includes UCSF Health, which comprises three top-ranked hospitals, UCSF Medical Center and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospitals in San Francisco and Oakland, and other partner and affiliated hospitals and healthcare providers throughout the Bay Area.