UCSF Patients Part of Nation's Longest Living Kidney Transplant Chain

Gabriel Baty and Olivo Cienfuegos probably never would’ve crossed paths if they each didn’t need a new vital organ to survive.

Baty, 40, is a scientist for the pharmaceutical company Novartis and lives in Albany. Cienfuegos, 61, is a retired factory worker who lives 80 miles away in Stockton.

But on December 7 they were lying just a few feet apart at UCSF Medical Center awaiting kidney transplants as part of the longest living kidney donation chain in history.

Neither man had a donor who was a match. But each had a family member willing to donate a kidney to a stranger, allowing them all to be part of chain which would, in turn, give Baty and Cienfuegos kidneys from other strangers. With 17 participating hospitals in 11 states, the chain consisted of 30 people willing to give up their kidney, matched with 30 more who needed one to survive.

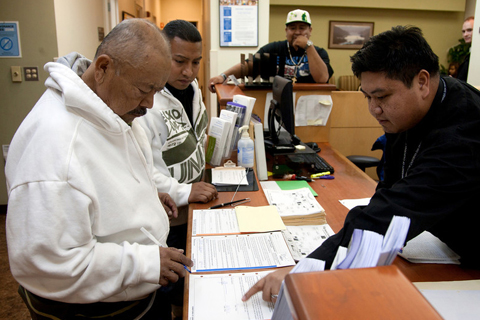

UCSF surgeons Andrew Posselt, MD, PhD and Ryutaro Hirose, MD, performed the transplants on Baty and Cienfuegos – just two of the 300 or so kidney transplants performed at UCSF every year, or twice as many as any other transplant program in Northern California, according to the United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS). The UCSF Kidney Transplant Program, established in 1964, performs more kidney transplants than any other medical center in the world. In 2010, UCSF opened the Connie Frank Transplant Center, a state-of-the-art facility caring for pre-and-post kidney transplant patients. The kidney transplant chain, formally known as Chain 124 by the National Kidney Registry, was recently highlighted in the New York Times and the San Francisco Chronicle.

Finding a Needle in a Haystack

This was Cienfuegos’ second kidney transplant, and according to UCSF transplant coordinator Janine Sabatte-Caspillo, RN, finding him a donor was like “finding a needle in a haystack.”

“Olivo is at a high risk for rejection because he has a lot of antibodies in his blood, which also makes it difficult to find a match,” she said. “He’s very lucky and it will be at least six months before we’re secure that the kidney won’t be rejected.” The first kidney, donated by his wife, failed due to diabetes and hypertension. He was relisted in 2009. His son Adrian, 29, donated his kidney to a 49-year-old Bakersfield woman on his behalf.

Baty’s story began 13 years earlier when his wife insisted he get a physical. As a seemingly healthy 27-year-old, Baty thought it was totally unnecessary. But that trip to the doctor ended up saving his life. Baty learned he not only had a torn bicuspid valve, but also a rare autoimmune disorder that ultimately results in kidney failure. The nurse, he said, told him she couldn't believe he hadn’t already dropped dead.

Baty had his heart repaired and later spent two years on dialysis. His wife Christy was unable to be a donor for medical reasons, but her mother, Yvonne Gordon, qualified. A stage four Hodgkins Lymphoma survivor, Gordon was inspired to donate her kidney after hearing a radio broadcast about another cancer survivor becoming a donor.

“I have a sticker on my refrigerator that says ‘She lives by what is the right thing to do,’” she said. “And that’s what I do every day of my life. It's given me such a wonderful gift to be able to help my children. I couldn’t love Gaby more if he was my own son.”

While Baty and Cienfuegos waited for their transplants, Cienfuego’s son Adrian was in surgery, donating his kidney to a stranger. Gordon had to wait another week to donate her kidney, which was flown to UCLA. “It's given me such a wonderful gift to be able to help my children," Gordon said. “It just takes one bridge donor to set up a lot of good. You can’t get more wonderful than that.”

Photos by Cindy Chew