The COVID-19 pandemic has touched every corner of our lives, so it stands to reason that we wonder what is in store for us in the coming months – and years.

I am an infectious disease fellow at UC San Francisco, and my colleagues, friends, and family often seek my advice. The questions I’m asked most often are about when life might return to “normal” and what is needed to get us there. Of course, it’s impossible to predict the future; the novel coronavirus – the agent that causes COVID-19 – is a pathogen humanity has never before dealt with.

And yet we are not entirely in the dark. After consulting several experts, I’ve come to see that the history of previous outbreaks is rich with lessons about what we might expect as we strive to bring the current one to an end – and how we can better prepare for the next one.

Adjusting to a new normal

The experts I spoke with anticipated at best a slow decline in COVID cases through the summer. Unfortunately, even that scenario may be optimistic, given the recent surge in cases in many hot spots around the country, combined with the fact that more businesses are getting the go-ahead to reopen. And even if we do see a downward trend, it will likely be punctuated by small outbreaks in places where people dwell in close quarters, such as nursing homes, jails, homeless shelters, and ships. Experts further predict that during the fall and winter – as schools reopen and holiday get-togethers are held, in places where they’re permitted – there will probably be an uptick in new cases.

Thus the challenge for scientists and policymakers alike will be to figure out the optimal timing and sequencing for reopening businesses and resuming our lives, while keeping cases from skyrocketing. “There are no scientific answers, so we have to look to history,” says Brian Dolan, PhD, a UCSF professor of anthropology, history, and social medicine.

Previous outbreaks caused by respiratory viruses, for example, serve as reasonable models for understanding COVID’s spread and predicting the impact of control measures such as social distancing and masking. These viruses, like the novel coronavirus, spread when an infected person coughs or sneezes, speaks, or sings. But they differ from one another in two important ways: how easily the disease can be passed from one person to another (its transmissibility) and the percentage of people infected with the disease that die (its fatality rate).

A century ago, an especially volatile combination of these two factors set off the 1918 flu pandemic, caused by an influenza virus, which sickened about one-third of the world’s population and killed an estimated 50 million people; that made its fatality rate about 2%, or 20 times that of the seasonal flu. We are seeing similar patterns play out with COVID-19. As of mid-July, the disease had sickened at least 12.7 million people worldwide and killed at least 566,000.

In 1918, as today, officials in many places mandated masks and issued stay-at-home orders. In San Francisco, for example, as Dolan recounted in a recent article about the 1918 flu in Perspectives in Medical Humanities, the Board of Health closed all public gathering places, including bars, theaters, and schools, on October 18. Four days later, the city’s mayor signed a bill requiring masks in public. The failure to wear a mask was punishable by imprisonment for up to 10 days or a fine of up to $100. Ironically, mask-related arrests resulted in a “congested” city jail, turning it into a breeding ground for influenza. (The 1918 pandemic was also marked, like COVID-19, by anti-mask protests.)

A line of people on Montgomery Street in San Francisco waits to get masks during the 1918 flu pandemic. Failure to wear a mask was punishable by imprisonment or a fine. Photo courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento.

Decisions to reopen society a century ago came in fits and starts. Only a month after enacting social-distancing ordinances, for example, San Francisco’s public health officer cited the decline of new flu cases as evidence that the disease had “virtually disappeared,” and on November 22, 1918, San Franciscans were allowed to ditch their masks. This decision unfortunately proved to be premature, as three weeks later, reports of new cases surged.

Protective measures were reinstated, then lifted anew in February 1919 as the city’s mayor weighed concerns for public health against the interests of business owners and a restless populace. Although the number of new flu cases increased between March and April 1919, that peak was not as high as the one the previous fall. By July 1919, the pandemic had abated, which experts attribute in part to the fact that, by then, it had been burning through the community for more than a year, conferring a degree of herd immunity.

In 2020, in hopes of avoiding the missteps of the past, California formulated a phased reopening. Spaces where the risk of disease transmission was considered lower, such as factories and outdoor museums, for example, got the go-ahead to reopen their doors first, as of May 8, to be followed by higher-risk spaces, such as movie theaters and gyms. Yet even that systematic approach wasn’t sufficient to stave off a new surge. By early July, California was seeing record daily numbers of new cases, impelling Governor Gavin Newsom to reimpose some restrictions. George Rutherford, MD, the Salvatore Pablo Lucia Professor at UCSF and head of the Division of Infectious Disease and Global Epidemiology, points out that lifting restrictions too early is tempting but perilous. “Stay the course,” he advises, “because otherwise we will see a big bump in the number of cases.”

But regardless of how adherent to public health guidance a particular populace may be, the ease and ubiquity today of international travel may undermine any singular locale’s efforts. “This is a virus that knows no borders,” says infectious disease specialist Peter Chin-Hong, MD, a UCSF professor of medicine. And even if international travel is blocked, interstate travel can easily spread the virus. For this reason, many states have instituted 14-day quarantines for visitors from other states or screening of travelers for signs of infection, such as a fever.

For many people in California, life is already starting to seem more familiar. Many non-essential workers have begun resuming shifts, and residents are returning to places of entertainment, exercise, and worship. According to Rutherford, however, large public events, such as concerts and sports games, likely won’t be permitted until 2021, when experts hope to have an effective vaccine.

Desperately seeking a vaccine

None of the experts I spoke with doubted that a vaccine against COVID-19 is inevitable. “There is a force of nature coming around this virus,” says Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, director of the UCSF Center for AIDS Research and medical director of the AIDS clinic at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. “Everyone in the clinical and research world has turned their attention to it.”

There is a force of nature coming around this virus. Everyone in the clinical and research world has turned their attention to it.”

One factor aiding the vaccine search is that, so far at least, the novel coronavirus appears to be relatively resistant to mutation – meaning that once a vaccine is developed, it’s likely to remain effective. This stability stands in marked contrast to the seasonal flu viruses, which mutate regularly. It is for this reason that the seasonal flu vaccine requires annual, rather than one-time, administration.

Yet the science of developing an effective vaccine is only the first in a series of challenges on the immunization front of the battle against COVID-19. The U.S. and many other countries lack sufficient infrastructure to manufacture and distribute a vaccine in the vast quantities that will be required. As Dolan says, “the ability to ramp up production and distribution to the scale needed is just not possible overnight.”

Figuring out the order of the distribution process is another challenge. It will be important to prioritize who gets the vaccine first, since there won’t be enough doses available to immunize everyone right away. Those given preference may include older people; people with depressed immune systems; and people with chronic health conditions, such as diabetes or lung disease. “We will have to have a very clear and realistic sense of who is at the highest risk of exposure to and transmission of COVID-19,” says Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, PhD ’94, MD ’99, MAS ’04, the Lee Goldman, MD, Professor and chair of the UCSF Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics.

Finally, even if enough doses can be manufactured and distributed to those who need them, convincing people to get vaccinated may prove challenging. That reluctance has been fomented partly by misinformation spread by the anti-vaccination movement. But for people who identify as Black, Indigenous, or of color, the reluctance to embrace a vaccine may also stem from mistrust of the medical system, which through a legacy of abuse, neglect, and unethical treatment of oppressed communities has sewn understandable fears.

Sadly, such communities are taking the biggest hit from COVID-19. [See “An Epidemic of Inequality”.] And disproportionately low vaccination rates would make this disparity even more pronounced. “In general, our adult vaccination rates are fairly abysmal, and we see big gaps by race and ethnicity,” points out Bibbins-Domingo, who is also the UCSF School of Medicine’s vice dean for population health and health equity. For example, Black people over age 65 are 10% less likely than non-Hispanic white people of the same age to have been vaccinated against influenza in the previous year, according to 2015 data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health. “We need to have a plan to address that,” she says.

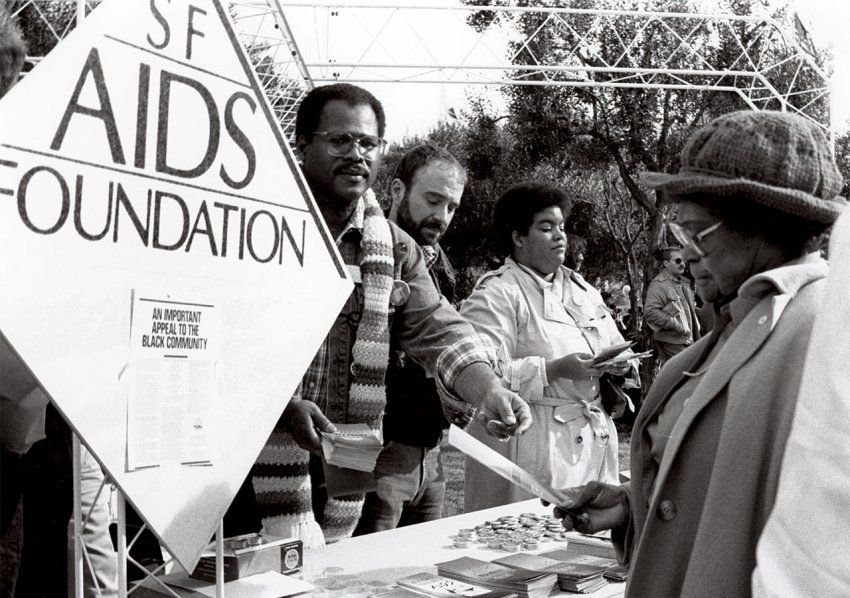

People hand out information about AIDS at an event in San Francisco in 1986. UCSF experts say communicating in a way that fosters public trust is an important lesson from the AIDS epidemic. Photo courtesy of UC San Francisco Library, Special Collections.

Ensuring that people get vaccinated will require clear, unified communications from the federal to the community level – something that has been a major challenge in the past, including during the AIDS epidemic. “One of the most important things is that we communicate what we know in a way that fosters public trust,” says Paul Volberding, MD, the Weiss Memorial Professor and director of the UCSF AIDS Research Institute. “That is probably the most important lesson from AIDS.”

There are key differences between the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes AIDS, and the novel coronavirus. For instance, HIV spreads through blood and sexual contact, and once a person is infected, the virus remains in their body for the rest of their life. Yet like COVID-19, HIV takes a particularly heavy toll on people who historically have been oppressed.

“The conditions that continue to drive HIV cases, such as poverty and injustice, all remain and are playing out with the COVID-19 pandemic,” observes Gandhi. That makes it all the more important that public policies and communication strategies address the structural inequities, such as overcrowded housing, and social determinants of health, such as lack of access to insurance coverage, that make vulnerable populations more likely to get sick and less likely to get vaccinated.

Insights from elsewhere

At the same time, even as the current pandemic is still raging, experts are giving thought to preventing – or at least mitigating – the next one. To this end, other countries’ experiences with COVID-19 and other infectious disease outbreaks are instructive.

The 2014 outbreak of Ebola in West Africa, for example, prompted the Obama administration to establish a permanent National Security Council team tasked with keeping an eye on the United States’ epidemic preparedness. This team, however, was eliminated in 2018. More recently, in late May of this year, President Trump announced that the U.S. would withdraw from the World Health Organization (WHO), which coordinates international health policy and alerts its 194 member nations about potential global infectious disease threats. Withdrawing from WHO has therefore left the country even less prepared to meet the challenge of future pandemics.

The 2014 outbreak of Ebola in West Africa prompted the Obama administration to establish a National Security Council team to manage U.S. epidemic preparedness, but the Trump administration eliminated the team in 2018. Photo: Andrea Tenner

This lack of preparation stands in stark contrast to South Korea, a country in which lessons from a previous epidemic have bolstered its responses to subsequent outbreaks. In 2015, South Korea was hit hard by MERS, or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, caused by another coronavirus. A major lesson South Korea drew from its experience with MERS was the importance of rapid and widespread testing. During that epidemic, all testing had to be sent to South Korea’s national disease-control agency. Consequently, the turnaround time for results slowed to 10 days. This backlog, in turn, led patients sick with MERS to hop from hospital to hospital seeking a diagnosis, says Seung-Youn Oh, PhD, an assistant professor of political science at Bryn Mawr College. Such diagnostic odysseys, she says, explain in large part why MERS spread extensively among hospitals.

So when COVID-19 arrived, South Korean officials were determined to make access to testing a priority. Early on, the country established numerous drive-through testing sites, as well as aggressive contact-tracing of anyone who tested positive. This approach helped quickly identify people who were infected before they could spread the disease further.

Following MERS, South Korea also developed a crisis management infrastructure, including a system for communicating health information among officials and between the government and the public. This infrastructure, together with mandated mask-wearing, allowed the country to avoid a lockdown in response to COVID-19. “Centralized leadership and clear chain of command was very important,” says Oh. Although South Korea was among the first countries to report a case of COVID-19, its death rate from the disease as of mid-July was only 5.6 per 1 million people. By comparison, Italy’s was 579.1 and the United States’ was 420.

New Zealand also has maintained a very low per capita death rate – only 4.5 per 1 million people as of mid-July. However, that nation took a different tack than South Korea, including a strict lockdown and very tight border controls. (One similarity with South Korea, however, was that New Zealand also ramped up its testing capabilities quickly.) In the United States, the response was closer to the one taken in New Zealand, focusing largely on stay-at-home orders.

But at least one UCSF expert, Dorothy Porter, PhD, a professor of anthropology, history, and social medicine, considers stay-at-home orders a “blunt, draconian, universal tool,” that has been used to contain disease for centuries. She recently wrote an article for Perspectives in Medical Humanities surveying the use of such orders from the time of the bubonic plague to the current crisis.

Mask-wearing has become the norm in South Korea. The lessons the country drew from the MERS outbreak in 2015 allowed the country to respond effectively to COVID-19 without crippling its economy. Photo: Wonseok Jang

Because South Korea didn’t require people to shelter in place during the COVID pandemic unless there was concern they were infected, Porter says, life went on as usual for most South Koreans, leaving that country’s economy relatively unaffected. “They didn’t have to close down their economy because they could just focus the quarantine on those already infected,” she explains. On the other hand, although New Zealand’s strict lockdown has had a significant economic impact, its restrictions have been so successful in tamping down the spread of the coronavirus that a recent poll showed 87% of residents approve of the way the government has handled the pandemic.

Politicians have to give more authority to health professionals and support their work, rather than spinning the pandemic for their own gain.”

One of the most significant differences between the United States and those two countries – which both achieved very positive outcomes, albeit through divergent strategies – is the United States’ lack of a coordinated, consistently applied strategy. Mask-wearing was mandated in some states, recommended in others, and mocked in a few. Stay-at-home orders were strongly enforced in some states, loosely followed in others, and not even considered in a few. The availability of testing, as well as of sufficient personal protective equipment, was also patchy. Greater coordination and consistency likely would have resulted in fewer deaths as well as less economic turmoil, experts believe. In addition, Oh advises that whenever another pandemic arises, barriers to test development and deployment should be eliminated much earlier, as they were in South Korea and New Zealand.

Yet perhaps the biggest obstacle to developing an effective response to a pandemic lies in turning a scientific issue into a polarizing political one. “The degree of politicization of the COVID-19 pandemic is really a fundamental problem,” Oh says. “Politicians have to give more authority to health professionals and support their work, rather than spinning the pandemic for their own gain.”

Facing the future

Addressing COVID-19 in this country for however long the crisis remains – and preparing for the next outbreak – won’t be easy. It will require developing strategies for infection containment, vaccine development and distribution, testing capability, contact-tracing infrastructure, and the production of personal protective equipment. It will also require careful consideration of which strategies to emphasize and then clear communication with government officials and the public.

A country’s culture also comes into play when confronting a pandemic. The willingness of a group of people to prioritize the common good over individual liberty affects how readily a populace is likely to adhere to tactics intended to control the spread of disease. Ultimately, policymakers will need to consider what we should do and what we have the political will to do whenever “next time” rolls around; they must give scientists and public health authorities a seat at the table, allowing these experts to offer advice, and then make the best recommendations they can.

For as any infectious disease expert will tell you: The question isn’t whether we’ll suffer another pandemic. The question is when.