Japan Earthquake and Tsunami One Year Later -- Lingering Impacts and Lessons

Tsunami waves crashed through windbreak trees and flooded the first floor of Choushunkan Hospital shortly after a 9.0-magnitude earthquake struck offshore on March 11, 2011. Photo by Hiroshi Nimura

A year after disaster struck, the Japanese public continues to be concerned about radiation contamination, cleanup, public health and the struggles of those in communities affected by the catastrophic earthquake, tsunami and Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor meltdowns.

Radiation Risks from Fukushima Likely to Be Less Than for Chernobyl

Experts who spoke at a daylong symposium at UCSF said earlier preventive efforts and less radiation release may produce fewer cancers.

Read story

Like people in the rest of the country and the world, Californians — including UCSF faculty, fellows and students — have pitched in to aid in relief efforts. But Californians are probably more likely than other Americans to wonder if similar disaster scenarios are likely to play out in the near future in the shaky Golden State.

On March 19 the UCSF departments of psychiatry and pediatrics and UCSF Global Health Sciences marked the anniversary of the disaster with a multidisciplinary symposium, “The Great East Japan Earthquake and Disasters: One Year Later,” featuring first-hand details from several who responded to the calamitous events.

Physicians who cared for those with medical and mental health needs in the disaster zone, experts who have studied radiation exposure and its health effects, an earthquake engineer and professionals who study disaster preparation and recovery worldwide met at UCSF’s Langley Porter Institute auditorium to present findings.

Craig Van Dyke, MD

In introductory remarks Craig Van Dyke, MD, a UCSF professor of psychiatry, noted that of the 300,000 people displaced by the disaster in Japan, many are still homeless. Some were displaced from ancestral lands where their families had lived for hundreds of years.

The March 11, 2011 earthquake and tsunami and subsequent reactor meltdowns changed people’s conception of tsunami hazards and nuclear power, Van Dyke said. Only two of 54 nuclear power reactors are still operating, and the remaining two are likely to be shut down. Opposition to nuclear power shows little sign of abating any time soon.

Japan's Matsumura General Hospital staff set up makeshift beds on the first floor of on the day the earthquake struck. Photo by Hiroshi Nimura

”The events had a profound effect on people’s mental state,” Van Dyke said.

Hospital Hardship and Tsunami Lung

When the earthquake and tsunami struck, Hiroshi Nimura, MD, who now directs the Kudan Clinic in Tokyo, was director of surgery at Matsumura General Hospital in the disaster-area town of Iwaki, a few miles inland in Fukushima Prefecture, barely outside the current zone evacuated due to radiation. He described the hardships faced by hospital workers and their patients, and in the nearby coastal Choushunkan Hospital, in the wake of the tsunami and earthquake.

Both hospitals maintained electrical power. Workers at Choushunkan Hospital heard the tsunami warning over the radio and evacuated the first floor, which was inundated, within 30 minutes. Nimura said they were able to vacate quickly because they had prepared according to guidelines from a Chilean earthquake emergency manual.

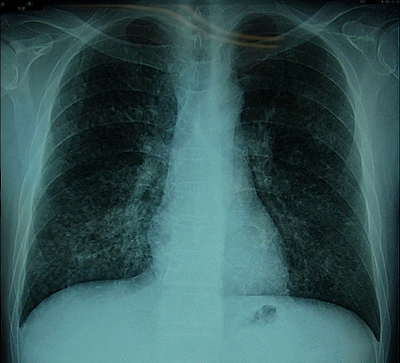

A Japanese patient with tsunami lung: During the tsunami rescue effort on March 11, 2011, a 51-year-old policeman was engulfed and nearly drowned, and he had injuries over his entire body. He was hospitalized near the coast and received oxygen therapy, and then was transferred to Matsumura General Hospital due to worsening symptoms. His limbs were cold, and his nails were discolored. An X-ray detected lung inflammation and pulmonary edema. He was given antibiotics, and his symptoms became less severe. Then Matsumura General ran out of antibiotics, so the patient was transferred toanother hospital. After two months of inpatient care, he was discharged. Photo by Hiroshi Nimura

Nimura made his way back to Matsumura General Hospital over several hours. The hospital was outside the tsunami zone, but suffered from non-structural damage. Uncertain about building safety, patients were first moved outside, but the staff who stayed on, fearing the effects of the cold, soon moved patients back inside again.

The hospital had a one-week supply of emergency rations — and a water-purifying plant and storage tank — but no running water. Major medications were used up within a week. Six of eight regional pharmacies with medications stored nearby were evacuated. Local ambulance service ceased due to a shortage of gas, but patients were transported to the hospital from private cars and helicoptors fueled from outside the area.

Communication was challenging. Cell phone calls and texting were not an option. Fortunately, the hospital’s internal phone system worked, and so did iPads running on a separate, 3G network, Nimura said.

Many people were treated for hypothermia. Caregivers also treated patients whose lungs were exposed to contaminated water and who contracted infections, a condition called “tsunami lung.” The staff treated these patients with a slew of antibiotics in the hopes that one of them would prove to be effective treatment.

Many from outside the area were reluctant to transport needed supplies to the hospital. There was no help forthcoming from the government for two weeks, according to Nimura. Hospital workers broadcast urgent messages via YouTube and Twitter and soon were able to make appeals for help through interviews with news media. It was three months before the hospital was again operating close to its pre-earthquake capacity, Nimura said.

Many buildings suffered significant non-structural damage. Shown here is Kawasaki Concert Hall outside of Tokyo, which was unoccupied when the earthquake struck. Photo by Stephen Mahin

Of the estimated 19,000 who perished in the disaster, most died from drowning or hypothermia, not from the crushing injuries that are most prevalent after most major earthquakes, symposium speakers said.

Earthquake and Tsunami Damage, Recovery and Resilience

As in other recent, major earthquakes, modern engineered buildings held up well, but the tsunami provided new lessons about structural vulnerabilities. Disaster recovery — including rebuilding commercial infrastructure, housing the homeless and restoring communities to economic health — typically takes about a decade, presenters said.

Stephen Mahin, PhD, director of the Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center in Berkeley, who led an invited delegation that visited Japan shortly after the disaster, said most modern structures survived the earthquake. Most of these modern buildings, apart from those that house lifeline services such as hospitals, now are designed to prevent loss of life, not necessarily to be usable immediately after an earthquake.

Structures older than about 20 years tend not to be built to the same standards and fared worse, but in general many structures survived better than expected, Mahin said. In addition, Japan has been thorough in retrofitting schools.

On the other hand, sea walls failed to contain tsunami waves, and wooden houses, bridges and other infrastructure that might have survived the 9.0-magnitude earthquake were destroyed by water and waves. The earthquake also caused substantial non-structural damage.

UC Berkeley professor of architecture Mary Comerio, MSW, MA, an internationally recognized expert on disaster recovery, compared the impacts of recent earthquakes in China, Chile and New Zealand. She said that national governments varied greatly in the ways they organized and administered disaster and housing relief. Following the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, China levied taxes in wealthier regions to aid relief efforts in poor earthquake-stricken regions. The central government and the army oversaw the re-housing of 5 million people in three years.

“Urban disasters are always housing disasters,” Comerio said.

Infrastructure designed to withstand earthquakes may still succumb to tsunamis. Photo by Stephen Mahin

According to Comerio, the poorest people to be displaced by disasters often are the last to find new homes in their communities. The Loma Prieta earthquake, about 100 times less powerful than the Japanese earthquake, occurred in 1989, but some public housing was never replaced, she said, and New Orleans after 2005’s Hurricane Katrina is demographically wealthier and less ethnically diverse.

Chile’s handling of the homeless after the 2010 earthquake was exemplary according to Comerio. “Chile’s flexible housing-recovery plan is really an excellent model of a centralized finance system with a broadly distributed system for engaging communities in decision-making.”

John Takayama, MD, MPH

Arrietta Chakos, MPA, a public policy advisor on urban disaster resilience who has directed hazard mitigation efforts for local city governments, outlined issues related to disaster preparedness. Chakos said that there needs to be much more community engagement and intergovernmental coordination of planning and implementation.

“Local communities bear the impacts of disasters before any level of government shows up,” she said. According to Chakos, updated policies from the Federal Emergency Management Agency indicate that “the federal government is finally admitting that they won’t be there to rescue us all.”

San Francisco is taking disaster preparedness seriously, she said, through the Resilient SF program. The city also is restructuring its water system. “For every dollar spent before disaster hits, we save society an average of four dollars,” Chakos said.

Rebuilding Lives

Van Dyke and fellow UCSF psychiatrist John Takayama, MD, MPH, previously traveled to Japan to help provide assistance following the disaster, and helped to organize other relief efforts undertaken by UCSF faculty, fellows and students.

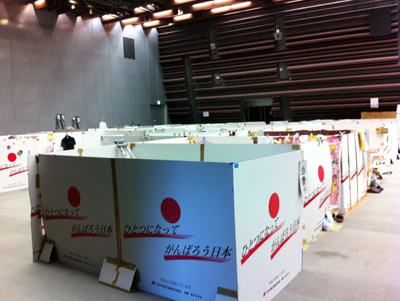

Residents in surrounding communities often stigmatized people who relocated to shelters and temporary housing after fleeing the tsunami or after evacuating radiation-contaminated areas. In addition to losing loved ones, their homes, communities and jobs, evacuees in shelters faced additional stresses due to overcrowding and lack of privacy. Mental health professionals offered services to populations traditionally uncomfortable acknowledging the need for such help, and organized local meetings with the help of community leaders to increase awareness of mental health issues and services.

Some Japanese evacuees living in shelters after the 2011 disaster resorted to cardboard boxes for a little privacy. Photo by John Takayama for UCSF

Three symposium speakers spoke about organizing and providing psychological support in the wake of the disaster. Takayama described UCSF involvement in providing mental health services and other forms of relief, including public service announcements.

Hisako Watanabe, MD, a pediatrician and child psychiatrist from Keio University School of Medicine in Tokyo, and Toshifumi Kishimoto, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Nara Medical University in Kashihara, both spoke about their work in impacted areas, including rural communities, where they evaluated the mental health of survivors and helped establish mental health programs for both children and adults. In rural communities especially, Kishimoto said, “We needed the cooperation of community leaders who knew who was in trouble.”

Before the talks on science and medicine, Jeffrey Bluestone, PhD, UCSF executive vice chancellor and provost, introduced Hiroshi Inomata, the consul general of Japan in San Francisco.

“We continue to be moved by the compassionate encouragement, support and assistance which the whole world has shown to us,” Inomata said. “In Northern California it is inspiring to see communities and people who still continue to support people who are victims of the disaster.”

“We must not only honor the memory of those who lost their lives, but we must also help rebuild the lives of those who are still suffering.”

Related Links:

Radiation Risks from Fukushima Are Likely to Be Less than for Chernobyl

UCSF, UCB and LBNL Scientists Discuss Fukushima, Medical Imaging Radiation Risks

UCSF Experts Aim to Provide Mental Health Services in Japan